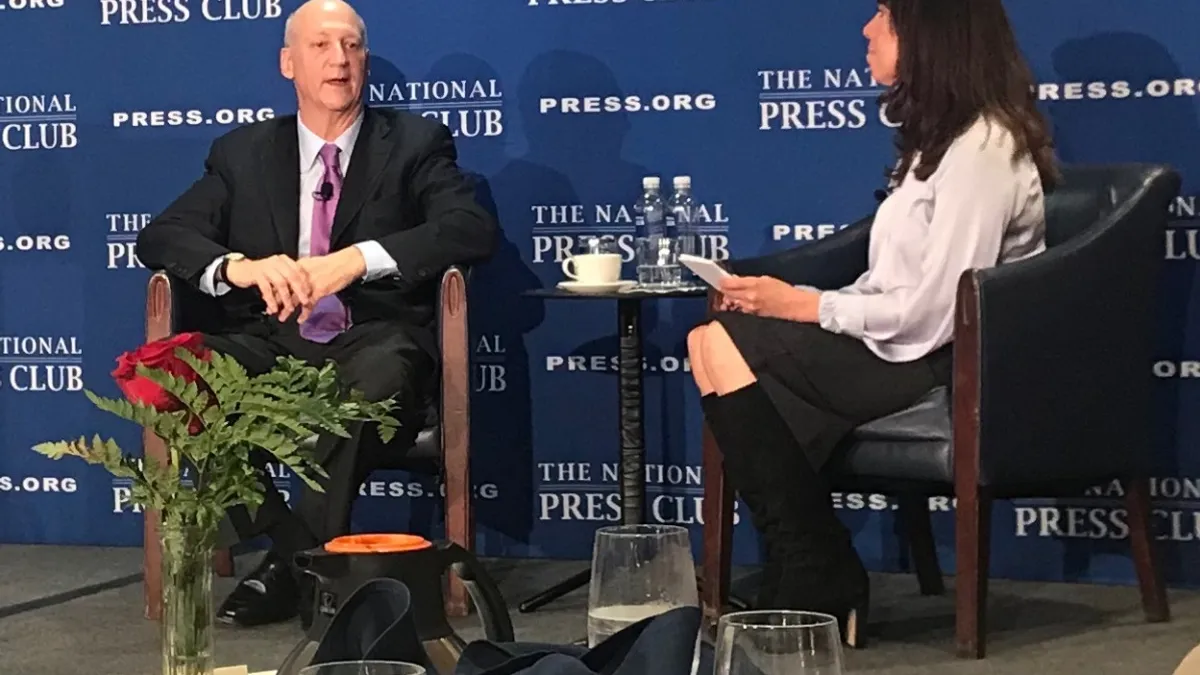

WASHINGTON — When Panera was a public company, its stock performed twice as well as Starbucks and six times as well as Chipotle, Panera founder Rob Shaich said during a National Press Club event last month. It had annualized returns of 25%.

But at the height of its worth in 2017, Shaich decided to take Panera private to protect its future. He said the public markets were too focused on short-term gains and were stifling innovation instead of thinking about the long-term future of the company.

"Nothing is proven until it is done, but activist investors don't have the patience to wait for that proof. They don't need to," he said.

These investors have been particularly focused on the restaurant industry of late. Last year, 20% of restaurant companies were hit by activists, he said. Activist campaigns have increased 18% annually since 2012, he said.

During 2018, activist investors led 240 campaigns targeting 218 companies worth more than $500 million, according to data from Lazard. Comparatively, activists targeted 169 companies in 194 campaigns in 2017.

Within the restaurant industry, full-service restaurants have been the particular targets of activism within the last eight months. Pressure from activist investors led Del Frisco's to consider a sale, and Bloomin' Brands CEO Liz Smith stepped down in April following pressure from investors. An activist investor is also pressuring Cracker Barrel to sell its fast casual spin-off to save costs. And J. Alexander’s has been swapping letters with an activist investor that has offered to buy the company claiming it could better run the company.

Why sell such a successful business model?

Shaich credits Panera's model with helping create today’s fast casual restaurant segment. The chain is one of the top 10 largest chains in the world and is pushing $6 billion in sales and employs 140,000 team members who serve one out of every 30 Americans, he said.

"We saw a large niche of customers who were rejecting fast food," he said. "They simply wanted something more than a lot of food for not much money. That was commercial. That was processed. What folks really wanted was real food. They wanted to be in environments [that] engaged with them and they wanted to be served by people who actually cared."

In 2011, the company underwent a dramatic transformation, expanding its technological capabilities and committing to serving clean food and building out its loyalty program. As of last fall, more than one-third of its sales are from digital and it has one of the largest loyalty programs.

When Panera was trying to innovate and adopt new technologies, it began to receive criticism from investors who felt the company didn’t need to transform and could outsource the technology instead of building it internally, Shaich said.

Panera was investing $150 million in online and mobile ordering but didn’t have any results to show yet. These investors also wanted Shaich to step down as CEO. Panera pushed back and won in both cases, but it wasn’t easy, he said. The company had to add $500 million in debt to buy back shares in 2015 to appease activist investor Luxor.

With pressure to perform, many restaurants have decided to go private and to no longer be under public scrutiny. Panera was one of them, and sold to JAB Holdings for $7.5 billion. At that time Panera had stocks worth $274 and had sales of $5 billion.

"They say it is lonely at the top … but nothing is lonelier than knowing that the very thing you spent your life working on could be disrupted by someone seeking short-term gain," he said.

Public markets weren't always this focused on short-term gains. But around 40 years ago, agency theory emerged out of the Harvard Business School that argued the only role of management is to serve the shareholders and deliver short-term success to maximize returns, he said.

Fifty years ago, the average holding time for a stock was eight years, he said. Today, it's about eight months.

The way activism works is an investor will buy 2% of company shares and then tack on 6% of derivatives, according to Shaich. The investor will then say it controls 8% of the company and that the board works for the investor, all in order to pressure the board to sell assets and cut costs, he said.

"They say it is lonely at the top ... but nothing is lonelier than knowing that the very thing you spent your life working on could be disrupted by someone seeking short-term gain."

Rob Shaich

Founder, Panera Bread

Many times management will just cave in because it’s not worth the fight.

"Management in so many instances find[s] the cost of fighting them is high and the probability of winning is low," he said. "You hear fear. Boards are trying to outmaneuver activists."

But what ends up happening, he said, is the boards begin to think in the short-term, like activist investors, and end up giving activists exactly what they want.

While selling Panera ended up being a good deal for shareholders, Shaich said taking it private with an evergreen investor also brought the company into an environment where it could have a long-term advantage and be isolated from short-term financial engineering.

"I don't believe a 35-year-old sitting in an office tower in Manhattan is better able to run the company than the folks that you hired to run the company," he said.

Fixing the markets

This pervasive short-term thinking is bad for the economy, Shaich said. Many business leaders are concerned that the focus is holding companies back on technology spending, hiring, research and development since they are too focused on meeting quarterly earnings expectations.

"GDP growth only happens when you have innovation," he said.

Companies can adopt differential voting rights to limit the rights shareholders have on voting. Tech companies, especially ones to recently go public, limited shareholder voting rights, making companies like Facebook virtually untouchable by shareholders. Facebook, in particular, has two share classes. Class-A shares have one-to-one voting rights while Class-B shares have one to 10 voting rights and are controlled by CEO Mark Zuckerberg. In 2005, 1% of companies to go public had differential voting rights similar to Facebook. In 2017, that jumped to 19%. Lyft and Pinterest also are offering two classes of shareholders right with their IPOs, and Google also chose a dual class of voting rights with its 2004 IPO.

Tax rates can also be adjusted based on holding years, such as what has been adopted in Europe.

Shaich said moratoriums on guidance can also reduce the pressure management has to meet quarterly expectations. So instead of providing it four times a year, it should be provided twice per year, but limiting guidance means a policy change would have to occur at the federal level. He said executive compensation should be based on long-term performance of a company instead of stock performance.

"We must continue to expect the long-term thinking if we expect American companies to continue to innovate," he said.