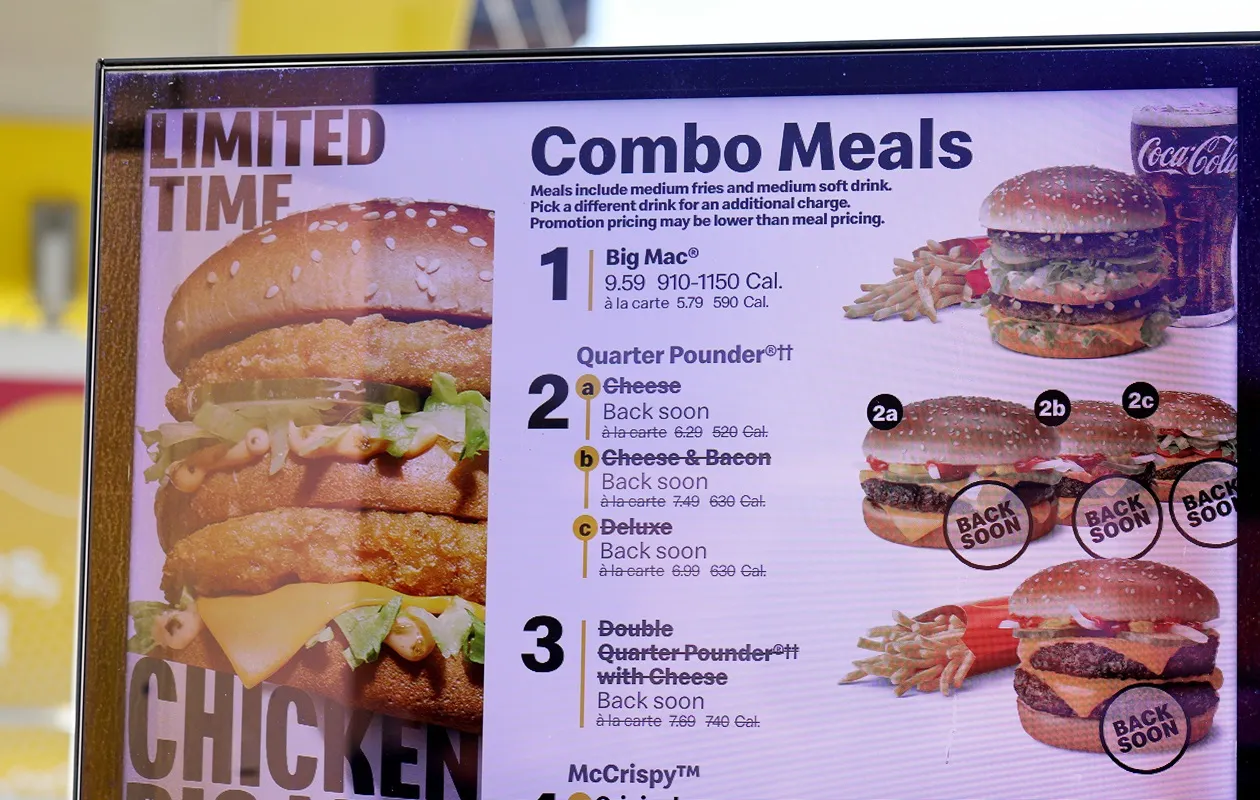

In late October, McDonald’s went through something that hadn’t occurred at the chain in over 40 years. The Golden Arches had to pull its Quarter Pounders off the menu due to an E. coli outbreak that sickened at least 90 people and killed one individual.

Regulatory agencies determined slivered onions from Taylor Farms were the culprit and the outbreak has been contained. Quarter Pounders have returned to 3,000 restaurants. In the weeks after the outbreak, questions remain regarding prevention, how this will impact customer sentiment and what suppliers and restaurants can do to protect themselves in the event of a similar outbreak.

“McDonald’s clearly does not take these things lightly,” said Phil Kafarakis, president and CEO of the International Foodservice Manufacturers Association. “They really did an exceptional job with managing how they controlled the situation.”

How McDonald’s scored on its supply chain preparedness

McDonald’s has trusted, long-term relationships with their suppliers and doesn’t put items out to bid or cycle through suppliers. While the company checks for redundancy and competitiveness, McDonald’s suppliers are integrated into McDonald’s processes, Kafarakis said.

“When something like this happens, they have a game plan,” Kafarakis said. “I think they executed exceptionally well, confining the situation.”

McDonald’s work alongside regulatory agencies was critically important, especially since some companies don’t like to share information until they know what is going on, Kafarakis said. Before the company located the source of the contamination, it eliminated Quarter Pounders from the menu because of initial concerns over the beef patties.

While McDonald's has generally received recognition for its safety record, the fast food giant could have done more to ensure that the food from its suppliers isn't contaminated, said Bill Marler, a personal injury lawyer who has represented victims of foodborne illnesses for more than three decades.

“They're the ones that bought the product,” Marler said. “If they can make their restaurants idiot-proof when it comes to cooking hamburgers, they should have made the same thing with respect to their supply chain.”

Although McDonald's may not technically be liable, the company could still see a reputational hit to one of its signature menu items.

“Nobody's going to remember that this E. coli outbreak was at whatever onion farm in Washington, they're not going to even remember Taylor Farms,” Marler said. “They're going to remember McDonald's Quarter Pounders.”

What food suppliers can learn

A lot of suppliers can learn from this situation because regulators are starting to clamp down on food supply and safety. The Food Safety Modernization Act, which creates additional instructions, traceability and compliance, was signed into law in 2011, and several compliance areas for produce will begin going into effect next year.

Even with brands that have multiple suppliers, it’s important to ensure everybody understands expectations and that everybody is trained and up to speed on the restaurant’s policies and protocols, Kafarakis said. Suppliers and restaurants should be integrated, interdependent and have checks in place.

This is particularly important as restaurants try new menu items and ingredients, Kafarakis said. Brands should ensure that new suppliers, or existing suppliers bringing in new ingredients, still pass quality assurance and adhere to the same protocols.

The situation should also teach small and midsize suppliers to check their protocols because if a large supplier can fail in this way, it could happen to anyone, Kafarakis said.

“Everybody wants to be better than the standard, and I think it’s important for consumers to know that,” Kafarakis said.

Who will ultimately be blamed for the outbreak has yet to be determined.

The CDC is investigating Taylor Farms' processing center in Colorado and an “onion grower of interest” in Washington state. Because of the complicated nature of supplier contracts, the main liability will likely fall onto the farm, Marler said.

“Part of the problem is that once McDonald's has a contract with Taylor Farms, they kind of wash their hands of food safety at Taylor Farms,” Marler said. “And then once Taylor Farms has a contract with their farmer, they kind of wash their hands of food safety at the farm.”

How restaurants, suppliers can insulate themselves from liability

Although the cause of the McDonald’s outbreak is under investigation, most cases involving E. coli in vegetables have been linked to contaminated agricultural water, including a major recall of romaine lettuce in 2018. Many large vegetable growers are located near livestock operations, which increases the chances for contamination.

Despite these material risks, there are many ways that suppliers and restaurants can protect themselves from economic consequences, including having proper insurance in place.

“Nobody wants to injure their customer. Let’s be clear about that,” said Glenn Drees, managing director of Food & Agriculture at global insurance brokerage Gallagher.

A restaurant needs to ensure that their suppliers have robust controls in place to reduce contamination, especially since E. coli can come from various places, including groundwater, manure used as fertilizer, or harvest machinery that wasn’t properly cleaned, Drees said.

“Generally, larger businesses have more sophistication in that area,” Drees said. “That’s not to say you’re more susceptible with smaller [suppliers.] It’s just less likely that they will have some of the sophistications.”

Large companies typically have more robust pathogen monitoring systems that some of the small suppliers might not have. Suppliers can change equipment design to make it easier to clean equipment.

Restaurant brands can also ask their suppliers to have product contamination coverage and possibly dictate limits, be it $50 million or $100 million, that would cover the impact of foodborne illnesses. That way, if a restaurant has to recall ingredients, clean the restaurant because of contamination and/or experience loss of business, they can turn to the supplier to cover these costs.

If a supplier doesn’t carry product contamination insurance, a restaurant should see if the supplier can cover these types of expenses.

“It’s something to try to get as much information as you can to see how you could be protected in the event of a loss,” Drees said.

Restaurants have product liability insurance as part of their general liability policies, which cover bodily injury or property damage because of negligence, Drees said. Product liability would pay out because of an illness suffered by a customer, while product contamination liability would cover loss of business or business interruption, and costs associated with recalls and things like hiring a media consultant to try and restore the brand.

Restaurants could also cook more of their ingredients, like onions, instead of serving them raw since cooking to a certain temperature typically kills pathogens associated with foodborne illnesses, Drees said.

Restaurants, especially large ones, can also include contractual language associated with contaminated products in their agreements with suppliers to protect themselves, Drees said.

Could McDonald’s have done more to reassure customers?

While McDonald’s did all it could to contain the outbreak, some experts said they could have done more to communicate with customers. McDonald’s executives said during an October earning call that it will work to regain consumer confidence and bring them back after traffic slumped in the wake of the outbreak.

Negative searches, which included keywords like “I got sick” or “terrible bad taste,” made up 8% of searches for McDonald’s on the day after the recall was issued, Issac Gerber, Captify’s global director of insights and analytics, said.

Captify uses site search data to understand what people are searching for on published websites. The company partners with 3 million websites globally and monitors close to 2 billion searches every day.

Initial negative searches were driven largely by consumers, including college students and parents of teenagers and young children, who were worried about the safety of their meals, Gerber said.

Negative searches peaked three days later on Oct. 25, at 15% of all searches for McDonald’s. This also represented an uptick in total searches for the brand, Gerber said, adding that the day after the incident there were about three times the total search volume as McDonald’s usually sees.

Negative searches shifted to reflect more concern among the business and investor demographics who were worried about overall earnings and the impact the outbreak would have on the quarter.

“Bad news travels so much faster than good news, so ultimately it’s very tough,” Gerber said. “I also think that the message didn’t break through on the platforms where the people who were worried about most would see the message.”

Gerber said it appeared that McDonald’s was focusing on the financial community, but that wasn’t the community who had initial concerns. It was customers.

“Thinking more about platforms like TikTok, Instagram Reels ... is where they should have started to reach their customer and then reach the investor,” Gerber said. “I think they did a good job of reaching that investor/business profile. I think they should have reached the customer first.”

Going forward, McDonald’s should put out a campaign dedicated to food safety, Gerber said, noting that this should help bring customers back.

“I think it would be a good idea for them to do a campaign dedicated to safety. I think that sort of thing will help them get the customers back into their stores.” Gerber said. “That’s going to be very challenging for them because they’ve not historically emphasized those values.”

It’s not easy to come back from an event like this either. Chipotle, which had years of food safety incidents, took a long time to recover its reputation and to create training programs for their employees to improve food safety, Drees said. It also released several campaigns to highlight their use of fresh ingredients and food safety elements.

“I’m sure that [McDonald’s is] not going to sit back and just let this thing blow over,” Kafarakis said. “They’ll have some messaging that relates back to ‘the food is safe.’”

Will McDonald’s E. coli outbreak have a lasting impression?

One of the first ever cases of E. coli in undercooked hamburgers was tied to McDonald's in the early 1980s, according to Marler. Up until the mid-1990s, producers could sell meat with common strains of E. coli, since the bacteria can be neutralized during the cooking process.

Congress moved to ban E. coli in meat after a massive outbreak at Jack in the Box sickened more than 700 people and killed four children. Marler, who represented the victims in the case, said congressional hearings and the emotional impact statements from those who lost children kept the issue in the spotlight.

Without sustained media attention, however, it's likely the McDonald's outbreak will be quickly forgotten in the fast-paced national news cycle.

“Consumers have a short memory, except for a handful of families who tragically lost somebody or has a permanent injury,” Marler said.