This article is the second in a six-part series exploring how major restaurant cities were impacted by the pandemic. Future articles will be posted here.

Snapshot

- Restaurant closures to date: At least 1,000 as of January, according to Eater NY

- Restaurant job losses to date: 122,400, or -48%, from March 2020 to January 2021

- Restaurant revenue losses to date: $10.3 billion, or -59%, from March to November 2020

"There is a lot of frustration about how the standards were applied differently and continue to be in New York City. Public health and safety has to be paramount, but a year into the crisis, we need to deal with the economic crisis."

Andrew Rigie

Executive Director, New York City Hospitality Alliance

New York City's restaurants are famous for offering patrons a taste of life around the globe without having to leave its five boroughs. But the pandemic has put the world's restaurant capital — once boasting over 25,000 eating and drinking places — at risk.

Without the city's nearly 70 million annual tourists visiting popular spots like Times Square or watching a Broadway show, many restaurants face an uncertain future. Operators in the core business district no longer have a vibrant office population to serve morning coffee, lunch or happy hour, either. And the situation won't likely improve for months.

Broadway isn't expected to start running shows until fall. As of early March, only 10% of the office workers in Manhattan have returned, according to a survey by nonprofit Partnership for NYC. By September 2021, only 45% of these employees are expected to fill the city's office buildings.

New York City's Open Streets: Restaurants program, which allowed restaurants to expand their outdoor dining into nearby parking lots, sidewalks and roads, has helped thousands of operators survive until this point. But a year of intermittent indoor dining bans and restrictions have taken a serious toll. According to a New York City Hospitality Alliance survey, 92% of local restaurants couldn't afford to pay their December rent.

With thousands of restaurants still at risk of closure, one of the biggest questions is whether the losses operators have suffered following months of indoor dining restrictions have helped slow COVID-19 rates.

How changes to dining policy in New York City affected COVID-19 rates

Similar to other major cities, New York City had a huge spike in cases early in the pandemic as experts were still figuring out how to mitigate the spread. While the city saw an over 2,600% increase from March 16 to April 16 — one month after all on-premise dining was banned — the case growth stabilized heading into the summer. At the end of June, when indoor dining restrictions remained, but outdoor eating was allowed across city streets, the percent increases of cases were in the single-digits month-over-month. Even when indoor dining was permitted across some, but not all restaurants at the end of September, cases increased about 6% in October and 11% in November. Dining room closures across all of NYC in December didn't seem to slow cases heading into January, however, when rates increased over 35%, similar to the increase recorded for May 16.

Based on contract tracing data performed on cases recorded between September through November, 1.43% of cases were due to exposures in restaurants and bars, with private household gatherings as the largest contributor to spread at over 73%, according to Eater New York.

"We've seen that highly regulated, reduced occupancy indoor dining has not been a major source of new COVID infections," Andrew Rigie, executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance said.

During the fall, NYC restaurants had to rely on Gov. Andrew Cuomo's Cluster Action Plan. This plan created color codes throughout the five boroughs, targeting areas across Brooklyn and Queens. Each color, which could change block to block, determined whether a restaurant could offer outdoor dining, indoor dining or were restricted to just off-premise.

"All the COVID restrictions were expensive and challenging to follow," Rigie said. "The color zones didn't really change the requirements; it just limited the amount of people you could serve and where."

The need for financial support

As restrictions deeply narrowed how restaurants could bring in revenue, both New York City and and New York state released several initiatives to try to alleviate this financial burden. Without government aid, the New York City Hospitality Alliance predicts one-third of the city's 25,000 restaurants will close permanently.

Restaurant-targeted support issued by city or state

- New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio signed legislation in May 2020 that included a COVID-19 relief package to provide assistance for restaurants, commercial establishments and tenants. The laws included caps on third-party delivery services, a suspension of sidewalk cafe fees through Feb. 28, and other commercial tenant protections.

- New York state partnered with Ritual to provide access to a commission-free digital ordering platform, Ritual One, to restaurants at no cost for pickup and delivery through April 2021.

- Gov. Andrew Cuomo's 2020-2021 budget proposal included $50 million for restaurants to rehire employees. Restaurants would be allowed to apply for a $5,000 tax credit for each worker they rehire up to 10 employees for a total grant of $50,000. Businesses have to prove they had loss of at least 40% to apply.

- The Empire State Development office created the NYS Bar Restaurant Recovery Fund in January, which offered $3 million in reimbursement grants for up to $5,000 for eligible restaurants and bars. Restaurants had to earn no more than $3 million in revenue in 2019, were in operation before March 1, 2019, and show they experienced financial hardship because of the pandemic. Franchises were not eligible. The program is no longer accepting applications.

"It's like getting punched in the mouth."

Spiros Chagares

Chef and owner, Arties Steak & Seafood

Up close: New York City's outdoor dining brought vitality back to the streets

For over 25 years, Arties Steak & Seafood has been an institution in New York City's City Island, a small neighborhood in the Bronx surrounded by the Long Island Sound. The restaurant, which is walking distance from the shoreline, serves an eclectic menu of seafood, meats, pastas and sandwiches.

When the pandemic struck in early March, Arties shut down for six weeks.

"It's like getting punched in the mouth," Spiros Chagares, Arties chef and owner, said.

During the closure, the restaurant lost all of its inventory, furloughed staff and had to reinvent itself, which meant transforming from a full-service restaurant to takeout only before expanding into outdoor dining as well.

"You have to consider your customers' fears, what the city allows and we had to move quickly," he said.

Chagares procured approval from the city for sidewalk usage and created a space complete with heat lamps, tables, chairs, lighting, dividers, umbrellas, oscillating fans, partitions and a music system. As winter set in and temperatures dropped, the restaurant constructed an awning to combat the elements and harness the heat, Chagares said.

In addition to switching to takeout only, Arties offered family-style platters with two and three-course meals. And when outdoor dining was allowed during the summer, Chagares brought back staff and sales were doing well.

"People flocked to see us in the summer," Chagares said. "They were so happy to see us reopen and doing business, but of course all that shifted again."

In early October, just eight days after indoor dining was allowed to reopen at 25%, Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued a zoned shutdown of select restaurants, and in December, indoor dining was banned indefinitely.

"It's been a roller coaster of a ride," Chagares said.

With dining rooms shut, Chagares had to make staff cuts again, some right before Christmas.

"It's heart wrenching to let them go," Chagares said. "We really had no choice, and they understand."

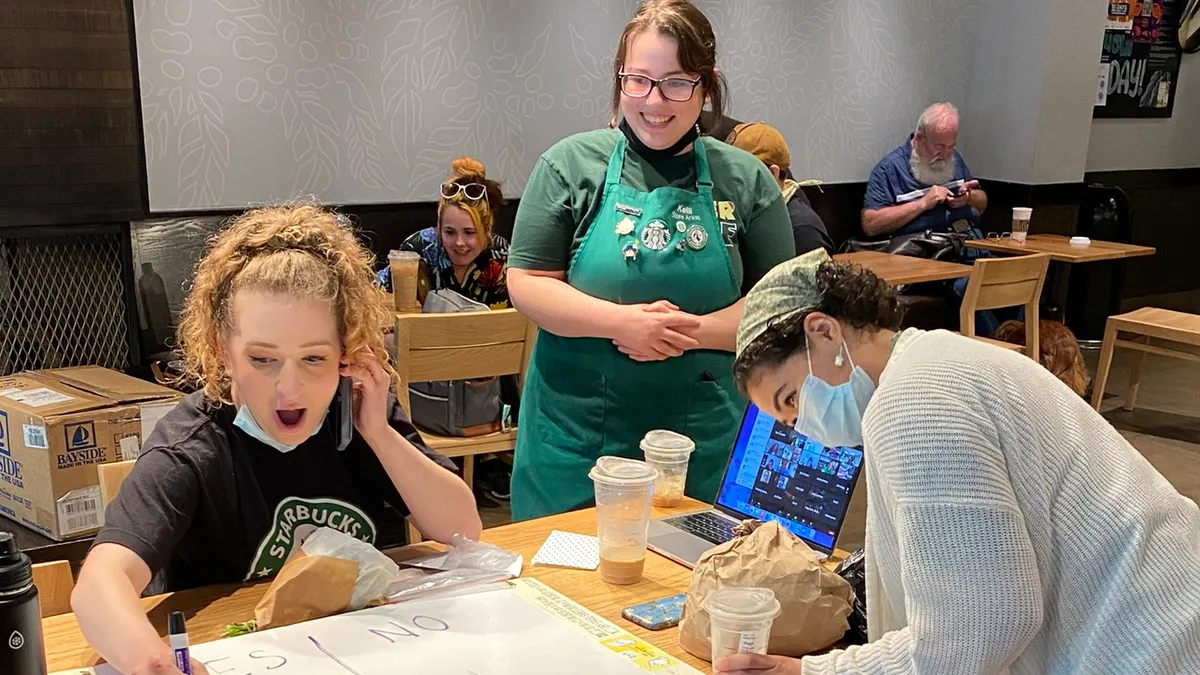

While NYC restaurants waited to reopen their dining rooms throughout last year, many relied on the city's outdoor dining program, Open Streets: Restaurants, which was turned into a permanent year-round program during the fall.

"It brought a critically important vitality back to city streets," Andrew Rigie, executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance, said. "People had been locked down in their apartments for months. It was able to bring people out to socialize and eat great food and drinks in a safe, socially distant way."

But less than half of New York City's restaurants, or about 11,000 restaurants, participated in the program, Rigie said.

"How helpful [outdoor dining] was was also based on how much outdoor space you had. If you were located on a corner, you can often set up in … the street and the sidewalk," Rigie said.

Restaurants had limitations if there was a bus stop, fire hydrant or other obstruction near their business, however, and operators with a narrow streetfront had less room to add outdoor seating, Rigie said.

"Outdoor dining was never intended to help save the industry," Rigie said. "It was intended to get a little more occupancy outdoors from what we lost indoors."

In addition to outdoor dining and takeout, restaurants offered meal kits, as well as merchandise like hats, T-shirts and other items to cover some of their losses, Rigie said.

"But it's all crumbs in the grand scheme of things, especially for full-service restaurants," Rigie said.

A roller coaster of dining room restrictions

Full-service restaurants were hit particularly hard by dine-in restrictions, which many felt were applied inequitably. Indoor dining capacity of 50% was allowed throughout much of the state since June, while New York City restaurants had to close their dining rooms in September. Many of the open areas around the state had higher infection and hospitalization rates than New York City, Rigie said.

Gov. Cuomo will allow New York City restaurants to increase capacity from 35% to 50% starting March 19 while the rest of the state will be at 75% capacity.

"There is a lot of frustration about how the standards were applied differently and continue to be in New York City," Rigie said. "Public health and safety has to be paramount, but a year into the crisis, we need to deal with the economic crisis."

Although indoor dining restrictions are easing, restaurants still need to space tables six feet apart and can't offer bar service, Chagares said. Under these restrictions, even if Arties were allowed to fully open indoor dining, it could only serve 50% capacity at best. Staffing levels would remain at 80% from its original staffing levels to accommodate logistics and maintain service quality, he said.

In addition to following strict guidelines, restaurants also had to contend with the Northeast climate, which made outdoor dining more challenging than it is throughout much of the country, Chagares said.

"We got the one-two punch in New York," Chagares said.

Saving restaurants with eviction moratoriums

While the crisis has been tough across the industry, it provided momentum to pass more pro-restaurant policies in New York City over the past year, Rigie said. That not only included the outdoor dining program but also a cap on third-party delivery fees, suspending enforcement of personal liability guarantees and leases, and a moratorium on commercial evictions, Rigie said. These policies, along with reduced fines, have helped give restaurants a fighting chance, he said.

"If [eviction moratoriums and suspension of personal liability] were not in place, countless restaurants would have been evicted and their owners would have had their personal assets seized," Rigie said.

But eventually both of these policies will end and the industry will have to face the looming rent crisis. If people haven't paid rent for most of the past year, Rigie said he doesn't know how the industry will make up those debts. Many landlords have mortgages and if tenants can't pay rent and landlords can't pay their mortgages, there could be default across the system, he said.

Currently the moratorium is extended through May 1. It's unclear how many restaurants are being artificially kept open because of the moratorium and the enforcement of the personal liability guarantees and leases, Rigie said.

"Right now it's all about how do we mitigate the loss and build back a more fair and equitable business climate that provides people opportunities to open businesses, work at restaurants and nightlife venues and go out and enjoy them," Rigie said.

Looking toward the future

While New York City has a long road to recovery, local restaurants have experienced some recent bright spots. Indoor dining reopened at 25% capacity in February, city infection and hospitalization rates have declined and warmer months are on the horizon, which will allow more people to enjoy outdoor dining, Rigie said.

Chagares plans to keep expanding outdoor dining with more tables as available, adding palm trees and plants to create a more seaport feel. He also will offer programming like wine tasting and cooking classes.

"It's wonderful to have life in the restaurant once more. There is a feeling of hope," Chagares said. "Customers and staff are excited to be back and are all being careful not to take any steps backwards. Maintaining a safe and stress-free environment will be key to making a recovery."

Vaccines will also be critical. New York City restaurant workers became eligible to receive vaccines after being included with a list of essential workers in February, but there still needs to be outreach in the industry to get as many restaurant workers vaccinated as possible, Rigie said.

How New York City's restaurant foot traffic shifted a year after the pandemic

The vaccine is a long way away from bringing things back to normal, however.

"Until the vaccine is being widely used, society won't get back to normal as we remember it," Rigie said.

Despite these ongoing challenges, Rigie expects New York City's nightlife industry to recover and that there will be a restaurant renaissance and a "new roaring 20s."

"When people can go out, places can open at 100%, people come back to their offices, tourists come back, people who lived in New York left and come back, there's going to be an incredibly powerful need to socialize, eat and drink," Rigie said.