The morning after the Elmwood Avenue Starbucks voted to unionize, customers lined up faster than drinks could be made, and nearly every table was full. Some patrons asked about the union. At the register, one customer gave his name as "the Union Makes Us Strong," another as "Solidarity Forever," and a third as "Workers United." Some of the store's employees wore union pins.

One day prior, on Dec. 9, an official for the National Labor Relations Board counted ballots for three separate elections at three Buffalo, New York area stores. Elmwood was the first location that was counted, and the only one where the union won an undisputed majority.

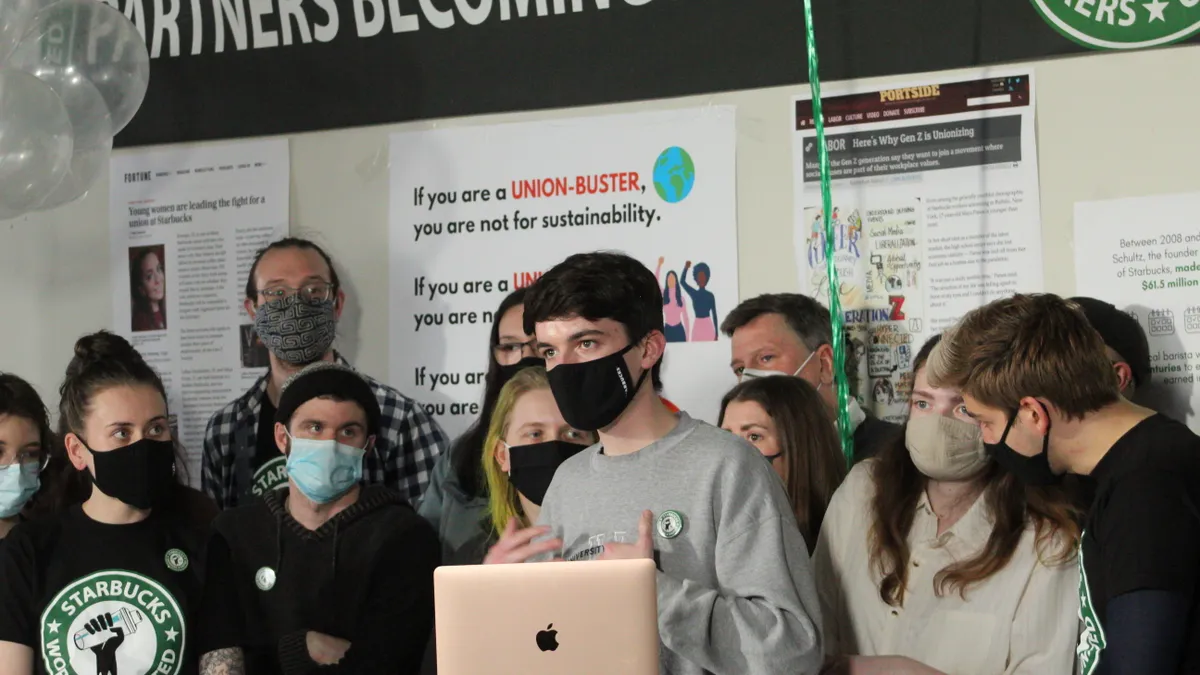

A group of workers from the organizing committee and a few union officials watched the count unfold from the committee's office on the fifth floor of an old Ford factory. Since late August, that office served as the nerve center of a campaign that drew national attention, and led some industry observers to predict dramatic changes in the American labor movement. But the course of the campaign shows restaurant labor is still constrained by the same legal and economic forces as it was before the pandemic.

Successful union drives, at least those resulting in NLRB elections, tend to follow a multi-stage process, with a period of secret or underground organizing followed by the initial public drive, which is then followed by the electoral campaign. After the election comes a period of contract negotiation. This can take many years. In Starbucks' case, it already has.

The seed for a union was planted in 2019

The union talk at Buffalo-area Starbucks stores didn't start in August 2021. Richard Bensinger, a professional organizer who helped Starbucks Workers United run a formal campaign, said many of the early members of the organizing committee were inspired by the drive to unionize Spot coffee, a Buffalo-area chain, in 2019.

In a Dec. 6 conversation with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Alexis Rizzo, a shift supervisor at the Cheektowaga Starbucks store and an organizing committee member, said discussions predated the Spot campaign two years ago, but shifts in working conditions and economic conditions made it possible to envision a successful drive at Starbucks this year.

"There's been some talk of unionizing among Starbucks partners since the day I started in 2015. But it was always a pipe dream. Because as hourly employees of Starbucks with such high turnover, we always felt disposable," Rizzo said. It wasn't until the pandemic worsened conditions on the shop floor and the labor market tightened in early 2021 that conditions were ripe for the campaign, Rizzo said.

These early conversations, and the relationships between workers before a campaign, are important factors in creating what labor historian Gabriel Winant describes as the mesh of solidarity. Winant, an assistant professor of history at the University of Chicago, said strong relationships between employees enable pro-union workers to trust each other under pressure applied by employers.

"It's easy to have those conversations when you're friends with people."

Casey Moore

Starbucks worker and organizing committee member

"It helps a lot to have…organizing leaders who either are drawn from that workforce and have organic leadership within it, or if they don't, at least are kind of recognizable," Winant said.

In July and August, Rizzo and other early leaders of the Starbucks Workers United organizing committee quietly built support among their coworkers and recruited them to join the organizing committee, which now numbers about 130 workers.

"The basic principle of the organizing committee is that it's good to have workers organizing each other as much as possible," Winant said. This keeps the union from appearing as an alien third party, as unions are often depicted by management. Further, Winant said, the period before a campaign goes public or petitions for an election gives the union the ability to build up majority support. Kimberly Cook, a member of extension faculty at the Worker Institute at Cornell University, echoed Winant's emphasis on organizing before a campaign goes public.

"The ideal is that you've done a lot of those conversations before the employer even knows it's happening," Cook said.

Once strong enough — or once discovered by management — the organizing committee takes the campaign public. At Starbucks, it seems the organizing committee managed to take the company by surprise.

"Corporate didn't actually find out until about 24 hours before we went public," Rizzo said. According to the organizing committee, the union had majority support at all three stores when it first petitioned for an election.

Starbucks put pressure on stores mulling unionizing, employees say

As soon as the campaign went public, workers with the organizing committee say they faced a sustained corporate campaign to wear down support for the union. At the heart of that pressure, workers said, was Starbucks' ability to control, surveil and access employees throughout their shifts.

"There's never a conversation that isn't getting overheard," Danka Dragic, a shift supervisor at a Cheektowaga, New York Starbucks store said. "I can't have open and candid conversations with my partners… they're only hearing from the company, they're only getting the anti-union works."

The first action the union organizers took once their campaign went public was to ask Starbucks CEO Kevin Johnson to sign a pledge agreeing to a set of principles the union argued was necessary to ensure a fair election. The union asked Starbucks not to make implicit threats, and to grant the union equal time at meetings held on company time, as well as equal ability to post pro-union information in break rooms and on bulletin boards. Johnson did not sign those principles.

James Skretta, a Strabucks employee at the Sheridan-Bailey store in Amherst, New York, told Restaurant Dive that subsequently, a flood of Starbucks support managers kept an ear out for what workers were saying. These support managers are still present throughout the Buffalo area as of Dec. 12, Brian Murray, a pro-union worker at a Starbucks in Lancaster, New York, said.

"We have managers wearing headsets, listening in on conversations. We have partners who are pro-union who are being isolated on the floor, to make it difficult for them to have conversations with their co-workers. And all of these things are obviously meant to intimidate us," Skretta said in a Dec. 8 interview.

"All it is, is scare mongering."

Danka Dragic

Starbucks shift supervisor and organizing committee member.

A spokesperson for Starbucks denied that the support managers, who he called support partners, were there to listen in on pro-union workers or disrupt union organizing. By contrast, the spokesperson said the support managers were there to improve training and offer extra help at understaffed stores.

Company higher-ups have had a number of meetings with individual workers. Dragic, and other organizing committee members, said the company was using those meetings to test the commitment of pro-union workers, and to single out shop floor leaders in the union drive.

Dragic met with Rossann Williams, Regional Vice President Allyson Peck and Regional Director of Operations Deanna Pusatier at the Courtyard by Marriott Buffalo Airport in September. Dragic asked Williams, in person, to sign the fair election principles drafted by the union. Williams declined.

Brian Murray, a pro-union worker at a Starbucks in Lancaster, New York, said Rossann Williams came into his store in mid-September while he was working the drive-thru. Murray felt Williams singled him out, shouting his name across the store before greeting other workers, and questioning him while he worked. Murray also asked Williams to sign the union's fair election principles. Williams again declined.

Williams also met with workers who oppose the union drive, like Dee Dee Clohessy, who works at a Buffalo-area Starbucks that has not filed for an election. Clohessy has been with the company for 18 years, long enough to see the children of regular customers grow up and start working for Starbucks. She said Williams was receptive to her feedback about the insufficient level of training for new partners, which Clohessy said often left new employees unprepared and overwhelmed.

In later meetings, Dragic said Starbucks implicitly threatened the benefits it provides employees by giving workers examples of benefits that could be lost in the course of collective bargaining. Dragic, and other partners, said the company told workers they could face serious consequences for violating Service Employees International Union's constitution once they had unionized.

"The more replaceable workers are, and understand themselves to be, the less likely they are to assert themselves."

Gabriel Winant

Assistant professor of U.S. History, University of Chicago

Starbucks also directly asked workers to vote against the union and brought workers to larger meetings where they shared anti-union talking points, workers on the organizing committee said.

According to Dragic and Murray, the pressure on pro-union workers didn't end with surveillance or one-on-one meetings with executives. Starbucks also began enforcing rules that managers had previously declined to enforce — such as dress code and language requirements — to target pro-union workers, they said.

"If you were wearing appropriate shoes and you looked put together, if you were wearing like a red shirt outside of a Friday, it wasn't going to be the end of the world. Now it's a write-up," Dragic said.

Murray was written up for wearing a pro-union shirt in November, and sent home from several shifts for wearing the shirt. A spokesperson for Starbucks, which has not disciplined workers for wearing union pins, emphasized that Murray had knowingly violated the dress code.

One of Dragic's pro-union co-workers, who had never received a write up before, received a final written warning for swearing under her breath in the back of the house.

"All it is, is scare mongering," Dragic said.

Corporate inflated voter rolls with anti-union employees, workers say

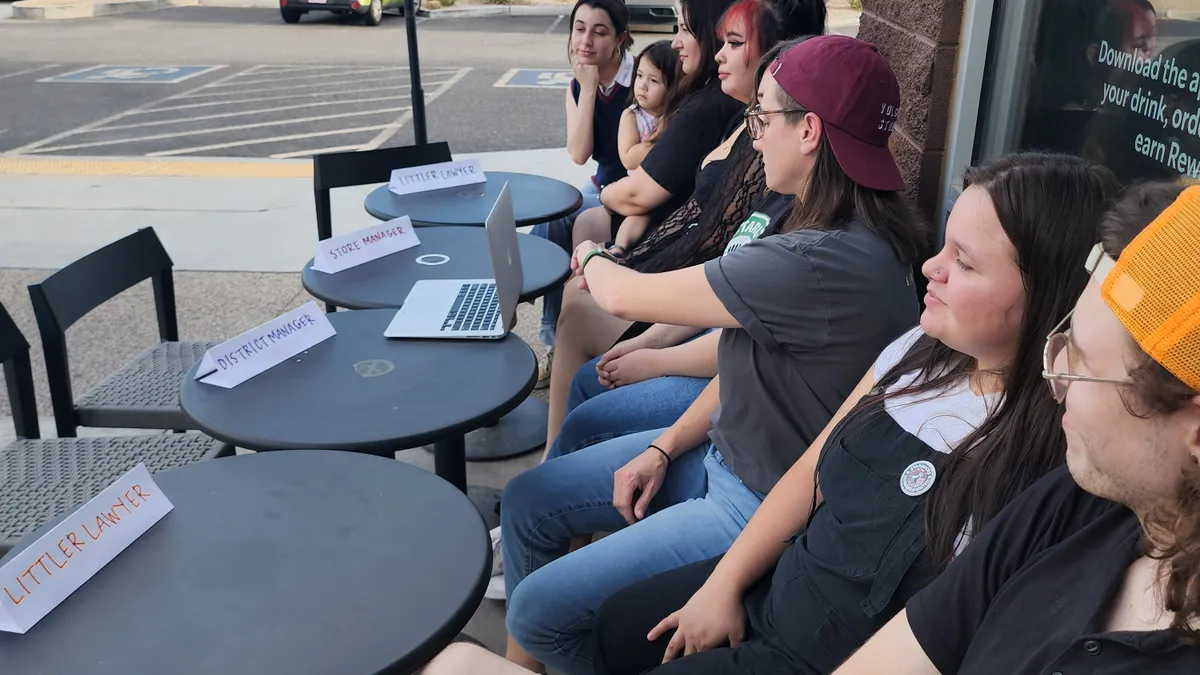

At Cheektowaga, the union filed with unanimous support, according to the organizing committee. NLRB documents show the union believed there were 21 workers at the Cheektowaga store on Aug. 30, when the petition for an election was submitted to the board. By the time the election took place, in November, the NLRB said there were more than 46 eligible voters.

A Starbucks spokesperson told Restaurant Dive that all of the workers the company included on its voter lists met the NLRB's requirements to count as employees at the Cheektowaga store at the time of the election. Two stores in the Buffalo market, however — one on Niagara Falls Boulevard and another at the corner of Walden Avenue and Anderson Road — closed temporarily, and their workers were sent to Cheektowaga. At least the Niagara store was closed for remodels, Cochran said.

"I didn't get a ballot. Nobody at my store got a ballot, I would've voted yes."

Colin Cochran

Starbucks worker and organizing committee member.

Starbucks allowed the diverted Niagara Falls employees to vote in the election, but the Walden/Anderson workers were barred from participating, he said.

"We really had no explanation for it," Colin Cochran, an organizing committee member from the Walden/Anderson store, said. According to Cochran, the Walden/Anderson store had a reputation for supporting the union, while the Niagara Falls Boulevard store did not.

"I might have worked there even a little bit longer than Niagara Falls Boulevard people. And... it wasn't just me, it was a significant group of people from my store," Cochran said.

"I didn't get a ballot. Nobody at my store got a ballot," Cochran said. "I would've voted yes."

The crowding at the Cheektowaga store reached absurd proportions, according to Cochran. Dragic, a shift supervisor at Cheektowaga, developed COVID-19 around the time of the peak staffing at that store, when more than twice the normal number of workers were on the clock.

"That was directly following having like 16 to 20 people in our store at a time," Dragic said. "I had not been exposed to 20 people in a group setting ever since the pandemic began."

Organizing outside the workplace helped secure a win, workers say

Ultimately, the organizing committee won an election at the Elmwood Avenue Starbucks, and managed to take a commanding — though not yet decisive due to ballot challenges — lead at the Starbucks in Cheektowaga.

Only at the Camp Road location in Hamburg, New York, did the unionization effort fail.

Before support managers entered the scene, according to union organizers, the store had filed with 80% support, which would translate to about 15 yes votes. Ultimately, the store voted 12 to 8 against the union, with 5 voters abstaining. Three votes at this store were challenged and one was declared void. Several ballots from Camp Road — potentially enough to sway the election — also went missing when a worker attempted to hand deliver them to the NLRB's office, claims union lawyer Ian Hayes.

So how did a few dozen workers and a couple of staff organizers for Starbucks Workers United, manage to do what no union had successfully done at any of the 8,000 corporate Starbucks locations in the United States?

"It doesn't matter how much money they spend, we're gonna win."

RJ Rebmann

Starbucks worker and organizing committee member

For Dragic, the campaign gave her a sense of meaning and community that was missing from her work.

"Prior to that, I swear for like a year I came home from work and I sat in my house. And I would talk to my roommate about how awful work was," Dragic said. "This is the first time that I'm, connecting with people that I'm working with at a level of… relating to each other on being human."

Other organizing committee members echoed this sentiment. According to some organizers, the campaign was forced to focus on organizing outside of work, at places where workers could talk without being overheard.

"We've kind of been forced to try to meet people outside of work in a lot of cases," Casey Moore, an organizing committee member, told Restaurant Dive. "It's easy to have those conversations when you're friends with people."

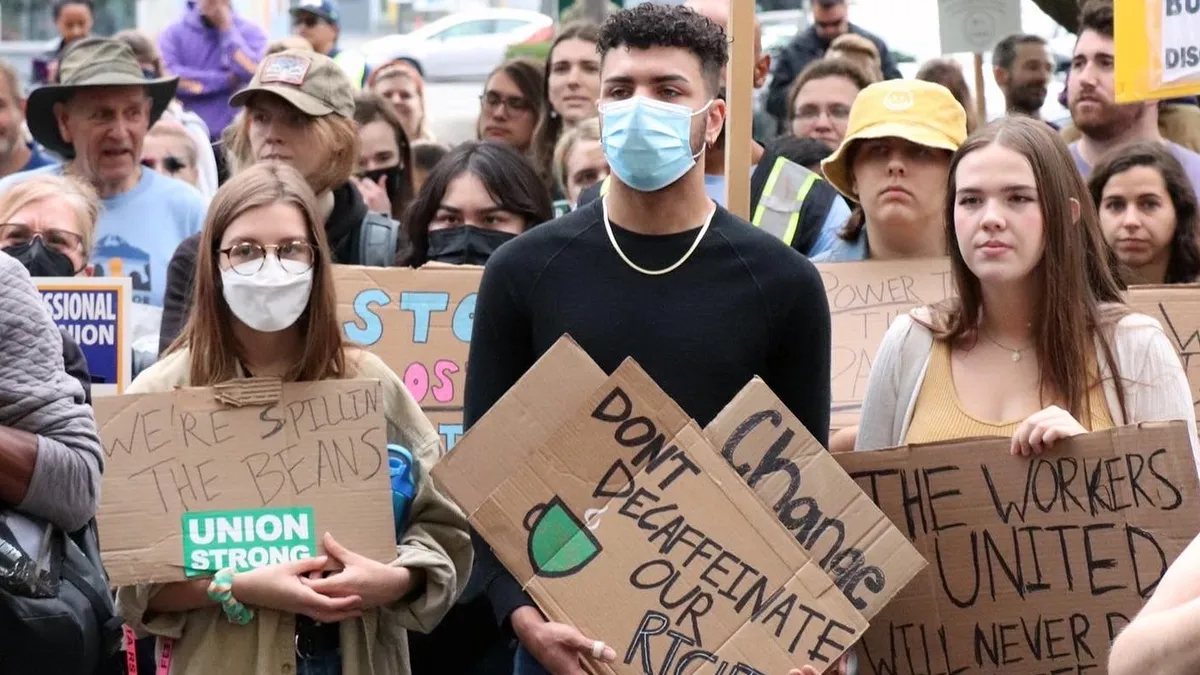

Community support also played a role. Dragic said customers would come in and voice support for the union.

India Walton, a democratic socialist who won Buffalo's Democratic primary but was defeated in the general mayoral election, was a vocal supporter. Support came from outside of Buffalo, too. Senators Chuck Schumer, Bernie Sanders, and Kirsten Gillibrand were all vocal supporters of the campaign, and multiple partners said Starbucks workers around the country would call in online orders for black coffee with pro-union messages.

Outside support, Winant says, plays a secondary but important role in reinforcing union campaigns.

The general macroeconomic conditions also played a critical role. As Rizzo told Sen. Sanders, the campaign only really kicked off in the summer of 2021, when the labor market was at its tightest.

"The more replaceable workers are, and understand themselves to be, the less likely they are to assert themselves," Winant said.

What this means for the QSR labor market

Some supporters of Starbucks Workers United were quick to call the victory at Elmwood historic, and to predict that it could herald a new day for organized labor in the U.S.

On Dec. 13, two Starbucks stores in Boston sent a letter to Kevin Johnson announcing their intent to unionize and urging him to agree to a set of fair elections principles. That brought the total number of Starbucks stores filing for NLRB elections to nine.

Cook said it would make strategic sense for Workers United to target markets with a high density of Starbucks shops.

"Take on New York City, for God's sake. There's [a] Starbucks on every corner and they're just filled with young progressive people," Cook said.

In terms of the Buffalo union drive's potential impact on organized labor, Winant said, "it makes sense to expect some positive reverberations in this and related industries, but not a wildfire sweeping the American labor market."

But Winant said the structural conditions of the QSR segment — its high turnover, employment split between corporate stores and franchisees and the ease of replacing fast food workers — would all constrain future organizing efforts that follow the Starbucks win. Within 6 months, the labor market could look completely different. The Federal Reserve, for example, has announced it will raise interest rates in 2022, which could increase unemployment, Winant said.

Starbucks also has a lot of power over contract negotiations, which could prove as important to future organizing as the elections process, but take years longer, according to Winant.

According to Cook, most union organizing drives never get a contract. Starbucks, Cook predicted, might drag out the negotiations. Winant said though it's hard to predict, negotiations could take at least a year if a contract is granted at all.

"They're not going to make it easy. They're going to try to drag it out, drag it out, and drag it out, so that people may never actually get a union contract… probably the majority of organizing drives end up never actually getting a contract," Cook said.

But on Dec. 9th, in the union office on the fifth floor of an old Ford factory, those problems did not seem so immediate. Surrounded by TV cameras, members of the organizing committee jumped up and down, and hugged each other when the Elmwood result was announced. They were subdued at the Camp Road vote result, but they still cheered at every yes vote. And when the yes vote took a commanding lead at Cheektowaga, they went wild again.

Soon, Dragic said, Starbucks employees will fill out bargaining surveys and get ready for the long struggle to negotiate a contract. To win a good contract at the Elmwood Starbucks, and potentially at the Cheektowaga Starbucks, would be another unprecedented victory for Starbucks Workers United.

"It doesn't matter what they throw at us," RJ Rebmann, a worker at the Cheektowaga location, said. "It doesn't matter how much money they spend, we're gonna win… When workers unite, when we show them the kind of power that we actually have, when we organize, there's no way that they can win."