Throughout 2023, restaurant workers scored major political victories, some of which could upend labor relations and significantly increase wages — and labor costs — in one of America’s largest industries.

AB 1228, the California fast food minimum wage compromise that takes effect in 2024, was the most significant restaurant policy change this year. But there were several other regulatory developments in 2023, which may indicate the direction of workplace regulation for restaurant workers in the coming years.

Chicago tosses subminimum wage

One shared thread among major policy changes this year was compromise between industry groups and progressive politicians. Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, a progressive labor leader, in May won his election on a platform that included the elimination of the tipped minimum wage. The city council’s first proposal to end the tip credit under Johnson’s administration would have taken effect by 2025.

Chicago Alder Timmy Knudsen, speaking at the vote to eventually kill the tip credit, said the version that ultimately passed — which will end the tip credit in 2028 — demonstrated the city’s willingness to work with the restaurant industry. The Illinois Restaurant Association, which lamented the death of Chicago’s tip credit, nevertheless accepted the deal as a compromise.

The law will cap Chicago’s tip credit at 40% of the city’s minimum wage on July 1, and shrink the allowable tip credit 8% annually over the next five years. One Fair Wage hopes this change will encourage more local governments to eliminate the tip credit, as California, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada and Oregon all have done. Washington, D.C. has moved to end the subminimum wage for tipped employees, as well.

California compromises with a $20 fast food wage

The most significant deal in American labor reform in recent years likely came down to a simple fact: No one wants to spend tens of millions of dollars and get nothing.

After California passed a major labor law reform (AB 257) in 2022, which would have set hourly fast food wages around $22 and established a strong regulatory council, the restaurant industry quickly raised $50 million to fight it through the state’s referendum system. Industry groups also began churning out research to frame the battle as one over inflation, rather than over pay.

The Service Employees International Union’s allies in the legislature began pushing for a law that would establish joint-employer liability. That law would make franchisors liable for some franchisee labor law violations, a major blow to franchised brands.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration went a step further and attempted to revive the Industrial Welfare Commission, a dormant state agency that would have had broad regulatory powers similar to the council set up by AB 257.

With organized labor and the restaurant industry both facing unpalatable possibilities, the National Restaurant Association, International Franchise Association, SEIU and the state cut a deal (AB 1228). This deal scrapped the IWC, the joint-employer bill, and the referendum, leaving workers with a $20 sectoral minimum wage set to take effect on April 1. It also establishes an advisory council with limited wage setting authority, in place of AB 257’s proposed powerful regulatory council.

The deal prompted major chains to plan for labor cost increases. Chipotle alone estimated the new wage rules would increase its wage bill by $74 million. The impacts of AB 1228 aren’t limited to QSRs, either, as chains like Denny’s noted on its Q3 earnings call. Though only fast food restaurants that are part of chains with more than 60 units nationwide are subject to the $20 minimum wage, this is likely to increase competition among employers for workers, driving wages up in other segments of the restaurant industry.

New York sets a $17.96 app-based delivery wage

In New York City, the long confrontation between delivery workers and delivery companies came to a head in a regulatory struggle over a proposed minimum wage.

New York cut its proposed target wage by nearly $4 dollars after delivery industry backlash. But this was not enough to avoid a court battle, and Uber, DoorDash and GrubHub sued the city. Despite winning a temporary injunction against the city’s $17.96 hourly wage for delivery workers, the aggregators’ efforts to overturn the law were scrapped when, at the end of November, a judge denied their moves to appeal their case.

DoorDash, in response, paused some driver incentive programs and pledged to hike fees.

The city’s ability to impose this wage on the delivery aggregator segment of the gig economy — a group of companies instrumental in defeating California’s effort to classify gig workers as employees — may make it more likely for other jurisdictions to impose similar regulations. Key to the city’s program is a provision that apps pay workers for on-call time or else compensate workers with higher pay for delivery time.

NLRB publishes joint-employer rule

In an interview with Restaurant Dive earlier this year, IFA CEO Matthew Haller described joint-employer rules — which would hold franchisors liable for franchisee labor law violations, treating them like employers — as an existential threat to franchising.

In October, the National Labor Relations Board issued a rule change that would treat franchisors as employers in many situations. In response, the IFA formed a law center specifically to fight the joint-employer rule and the Restaurant Law Center and U.S. Chamber of Commerce sued to stop the NLRB from implementing the rule. The NLRB delayed implementation from December to February, but legislators from both parties have invoked The Congressional Review Act, a law giving Congress the authority to overturn specific federal regulations within 60 session days of the promulgation of a rule.

The CRA measure did not come up for a vote in the 2023 session, but the CRA includes a look-back provision.

Under that provision, “the periods to introduce and act on a disapproval resolution… reoccur in their entirety in the next session of Congress, beginning in each chamber on the 15th day of Senate session and the 15th House legislative day.” That procedure applies if the previous session ends without a vote on the measure and Congress adjourns sine die — as Congress does each year, according to the Congressional Research Service.

As a result, the legislative fight over joint-employer regulations may resume early next year and last deep into 2024, with the outcome dependent on procedural maneuvering by individual legislators.

The NLRB and Senate HELP committee try to discipline Starbucks

One long-running restaurant story during the Biden Administration has been the NLRB’s efforts to strengthen U.S. labor law.

The Starbucks Workers United campaign, with its national scope and hundreds of unfair labor practice complaints, has been key in the agency’s moves to strengthen labor law.

In particular, the NLRB regional offices and administrative law judges have challenged Starbucks’ addition of benefits that excluded union workers. In September, Starbucks pledged to challenge this finding. The agency holds that Starbucks violated labor law and effectively promised workers benefits in exchange for voting against unionization. Starbucks said the agency’s allegations broke with traditional definitions of unfair labor practice. The company has maintained that it is required to bargain over changes to working conditions.

“Starbucks did not engage Workers United or other unions about providing the benefits to stores where employees had voted for representation,” the company’s own independent review found. When Workers United attempted to waive the obligation to bargain, “Starbucks stated that it was ‘unwilling to remove isolated [mandatory bargaining] subjects from the bargaining process.’”

In the summer, the NLRB instituted a new rule to speed up union elections.

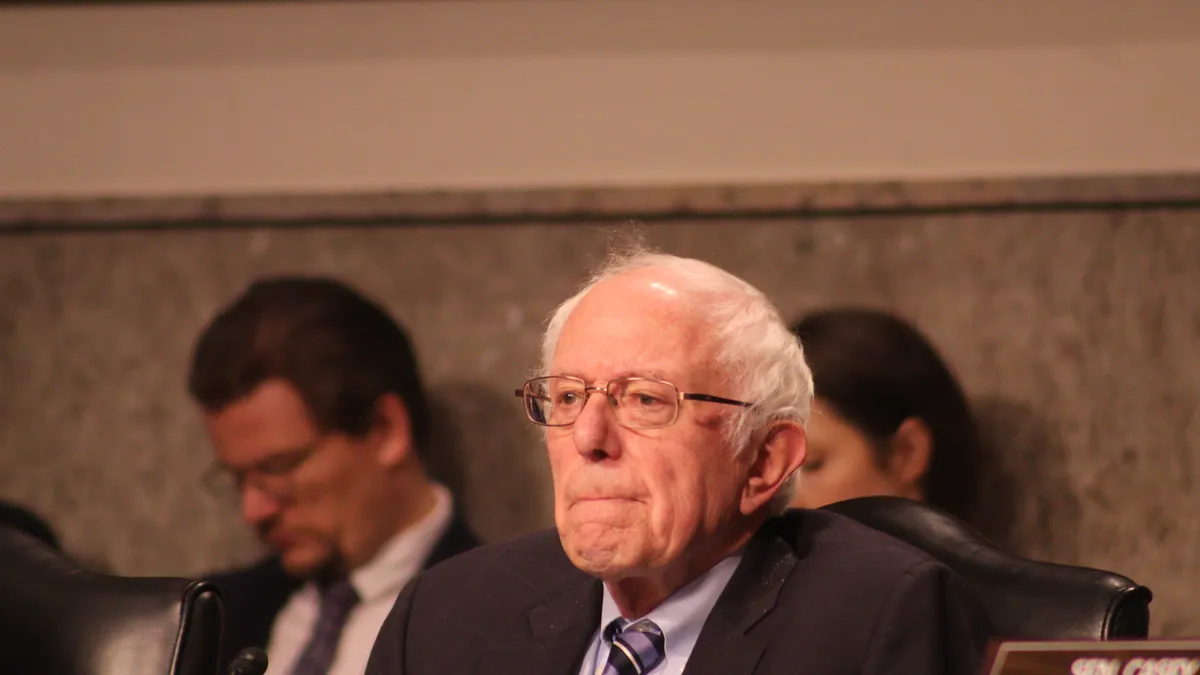

In late March, Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee Chair Bernie Sanders (I-VT) brought Howard Schultz before his committee to ask about Starbucks’ response to unionizing workers. The committee generally failed to press Starbucks on the legal issues raised by its response to SBWU. Schultz largely repeated the same general statements Starbucks spokespeople gave Restaurant Dive over the last two years. But the direct attention from one of the Senate’s permanent committees on a single company’s reaction to union organizing signaled labor law as a political priority for the majority party.