In early 2022, Starbucks Workers United seemed unstoppable, reaching 100 store election filings in mid-February. The coffee chain’s strategy of flooding stores with support managers to quell labor organizing failed in Buffalo, New York, fueling more employee support for the union.

Howard Schultz returned as interim-CEO in April, and Starbucks excluded union workers from benefits increases the following month — a move consider a legal gray area, depending on its motivations. SBWU persuaded a regional office of the National Labor Relations Board to issue a complaint against the company’s actions, but the NLRB’s limited power meant this move was a mostly symbolic victory.

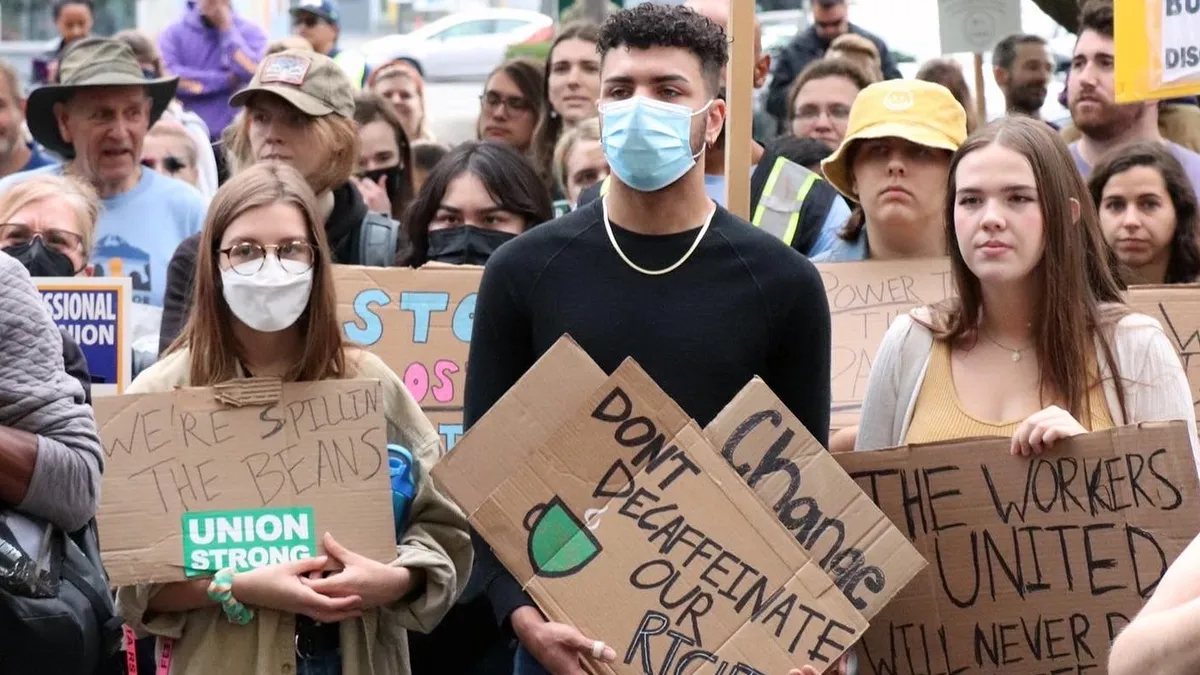

SBWU changed tactics as it won more stores. Strikes, walkouts and demonstrations grew more common. The union accused Starbucks and its managers of a deluge of anti-union activities: deliberate understaffing, retaliatory firings of union supporters, closure of union stores, and even false kidnapping accusations. Most significantly, though, the union pointed to the company’s refusal to extend its new benefits as foul play. In Boston, frustration over schedule policies and conflict with a new manager sparked a 64-day strike at one cafe, with both the union and Starbucks claiming victory.

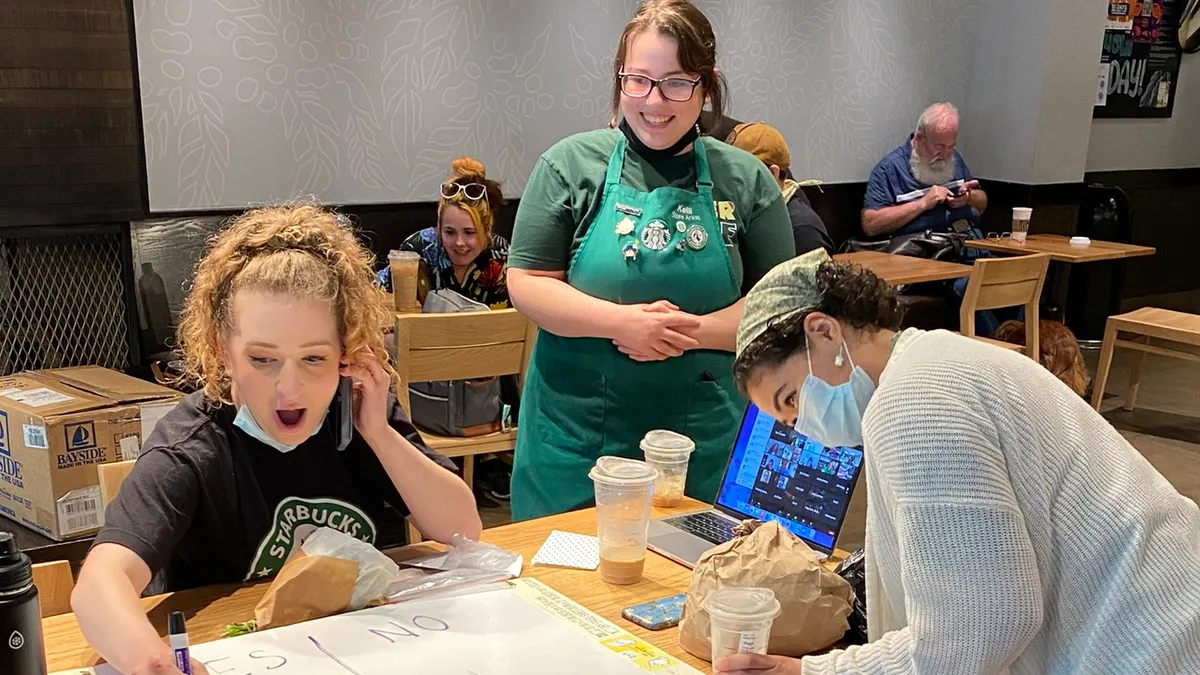

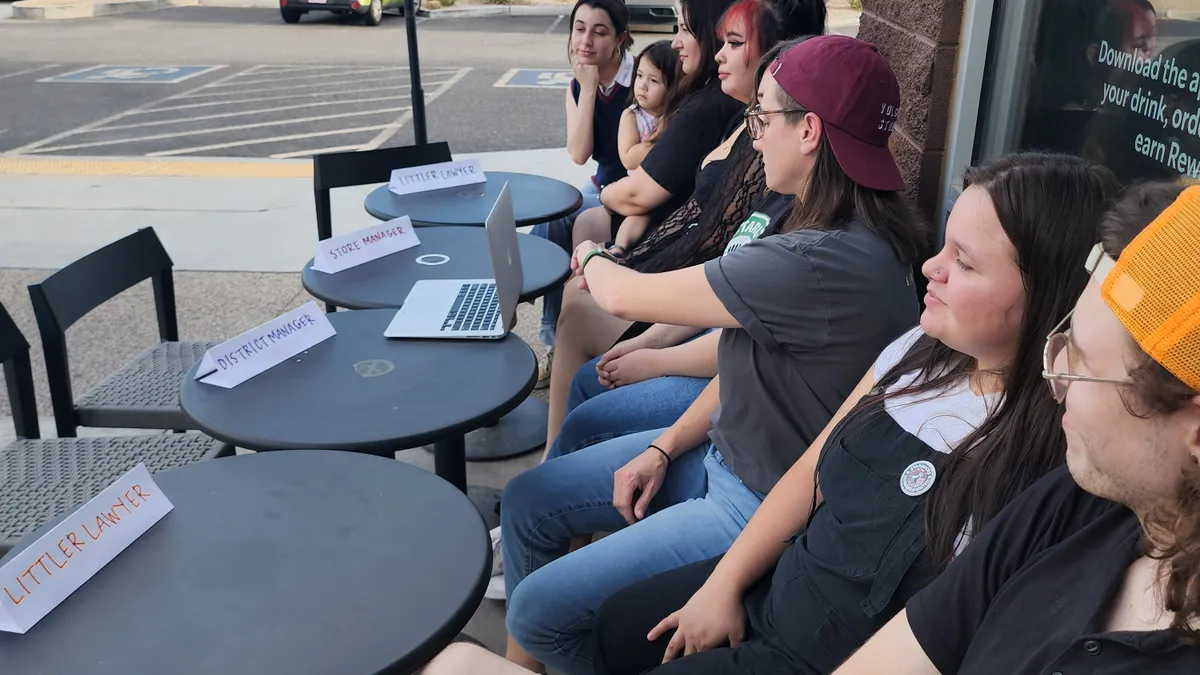

In the fall, the company and the union both declared their willingness to bargain for a contract. But the first sessions ended in a matter of minutes as Starbucks representatives walked out over the union’s inclusion of bargaining committee members using videoconferencing software. Now, the union is fighting the clock, as the one-year period preventing decertification challenges from undermining SBWU’s early wins dwindle.

Starbucks workers told Restaurant Dive they wanted to transform labor relations at the coffee giant, seeking just-cause protections, clearer discipline, greater control over workplace issues and meetings between worker-management committees. But there are more prosaic issues at stake for SBWU too. Workers want wage increases, the ability to turn off mobile orders, better equipment, reimbursement for uniform expenses and more COVID-19 leave.

By December, Starbucks Workers United sought to expand the scale of its fight with the company, organizing two national strikes that each impacted more than 100 stores, staging demonstrations with other unions and organizing a trial-run boycott of gift cards.