Dive Brief:

- Starbucks’ attorneys will appear before the United States Supreme Court on Tuesday to ask the high court to change the tests several circuit courts use when evaluating National Labor Relations Act Section 10(j) injunctions sought by the National Labor Relations Board, the company announced last week.

- Section 10(j) injunctions are temporary court measures enjoining employers or labor organizations to stop alleged unfair labor practices while the NLRB reviews those practices through its lengthy process of investigation. If Starbucks prevails, the court would instruct circuit courts to use a more stringent, four-factor analysis of 10(j) injunctions used by four judicial circuits courts, in comparison to a two-factor test used by five circuits and a hybrid test used by two.

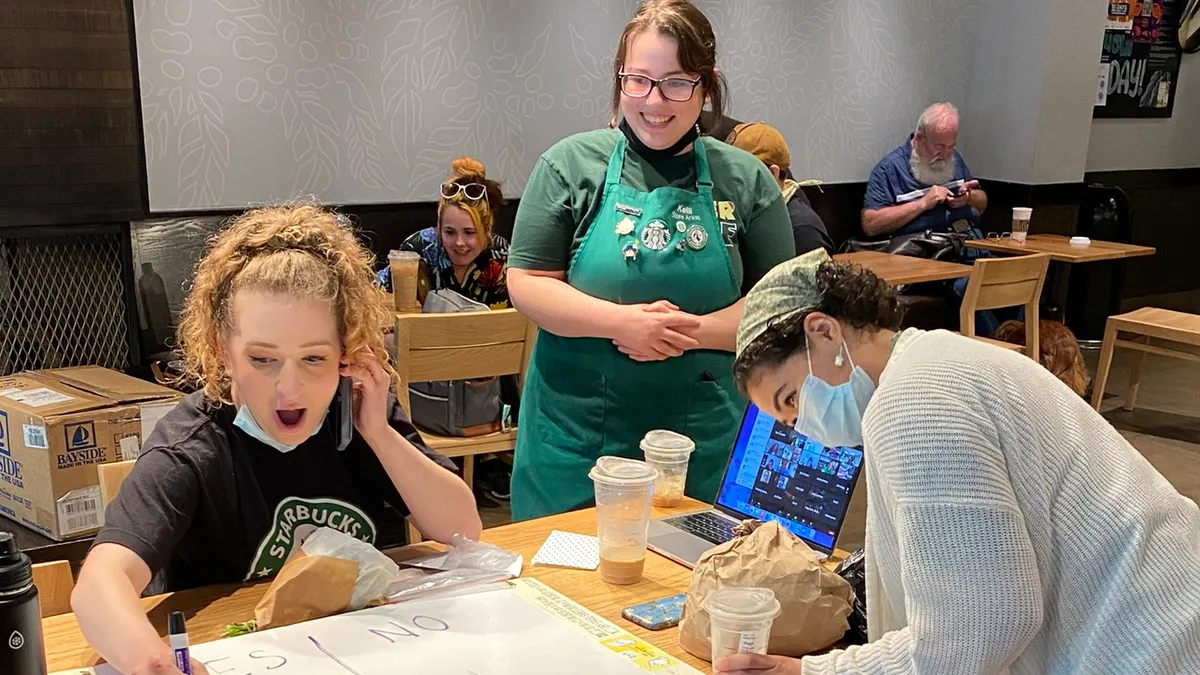

- Starbucks said the four-factor test would have altered the outcome of the federal court battle over the reinstatement of seven Starbucks Workers United members fired in Memphis, Tennessee and later reinstated following an injunction.

Dive Insight:

Starbucks said it was acting on behalf of U.S. employers and was joined in a series of amicus briefs by a variety of employers associations,

John Logan, chair of the labor and employment studies department at San Francisco State University’s Lam Family College of Business, said 10(j) injunctions are a key tool for the Board because the federal court injunctions can halt, or remedy, unfair labor practices like retaliatory firings, while the Board’s multi-step, sometimes years-long process for resolving ULPs churns along.

Logan said that applying a more stringent standard would weaken workers rights and make it more difficult for workers seeking union representation to get it in cases where workers are fired and ultimately reinstated, which is what took place in the specific instance with which this case originated during SBWU’s campaign.

Jaz Brisack, a founding member of Starbucks Workers United, said the company’s decision to take the case all the way to the Supreme Court was an example of a longstanding contradiction between the progressive reputation it seeks to cultivate and its legal actions. Brisack said Starbucks has made use of Trump-appointed conservative judges to attempt to rewrite labor law in favor of employers.

Logan echoed the sentiment, stating the company was trying weaken one of the key enforcement mechanisms for the NLRB, an obvious conflict with an attempted detente with organized labor. In February, Starbucks and Workers United announced they would resolve some litigation and set up a framework for bargaining. Sources at the company and union say the first major bargaining session will happen later this week, and include more than 150 worker delegates in-person and 250 more in caucusing.

Starbucks, in a statement emailed to Restaurant Dive, said the case “has no bearing on our commitment to a mutually constructive path forward with Workers United, our shared commitment to resume bargaining this week and our aim to reach ratified contracts in 2024.”

Jennifer Abruzzo, general counsel of the NLRB, explained the necessity of 10(j) injunctions in a statement emailed to Restaurant Dive.

“Without obtaining this temporary relief, the lawbreaker will fully reap the benefits of having violated workers’ rights—such as by snuffing out a nascent organizing drive—through the passage of time, because a Board remedy in due course will come too late to sufficiently address the harm,” Abruzzo wrote.

Abruzzo said that the difference between tests was insubstantial, however, and pointed to the NLRB’s record of obtaining injunctions in circuit courts using the more stringent four-factor test Starbucks is pushing for. But the court records show a more ambiguous outcome.

In 15 cases since 2021 in which the NLRB sought 10(j) injunctions under the more stringent four-factor test, the agency prevailed 10 times, lost four times and secured a partial victory. In two-factor courts, the NLRB won six and partially won a seventh case, out of seven total cases.

Starbucks Workers United declined to comment when asked if it had communicated with Starbucks regarding this case. The union is not a party to the case. As part of the union’s framework agreement with the company announced back in February, some litigation — over the company’s refusal to extend new benefits to union stores and over the union’s pro-Palestine Twitter posts — between the two parties was resolved.