Last summer, Starbucks’ interim CEO Howard Schultz insisted the company’s board leave two chairs empty at its meetings — one to symbolize the presence of customers, and a second to represent workers. At the start of the campaign, workers told Restaurant Dive they wanted more than a symbol. They wanted a real seat at the table. Now, the union’s noneconomic contract proposals would give workers a say in the day-to-day management of the company.

Starbucks Workers United has put forward 15 non-economic proposals for changes at Starbucks on its social media pages. In union bargaining, noneconomic proposals exclude pay-related issues like wages and benefits and focus on topics like health and safety, dress code, seniority rights and nondiscrimination policies, in SBWU’s case.

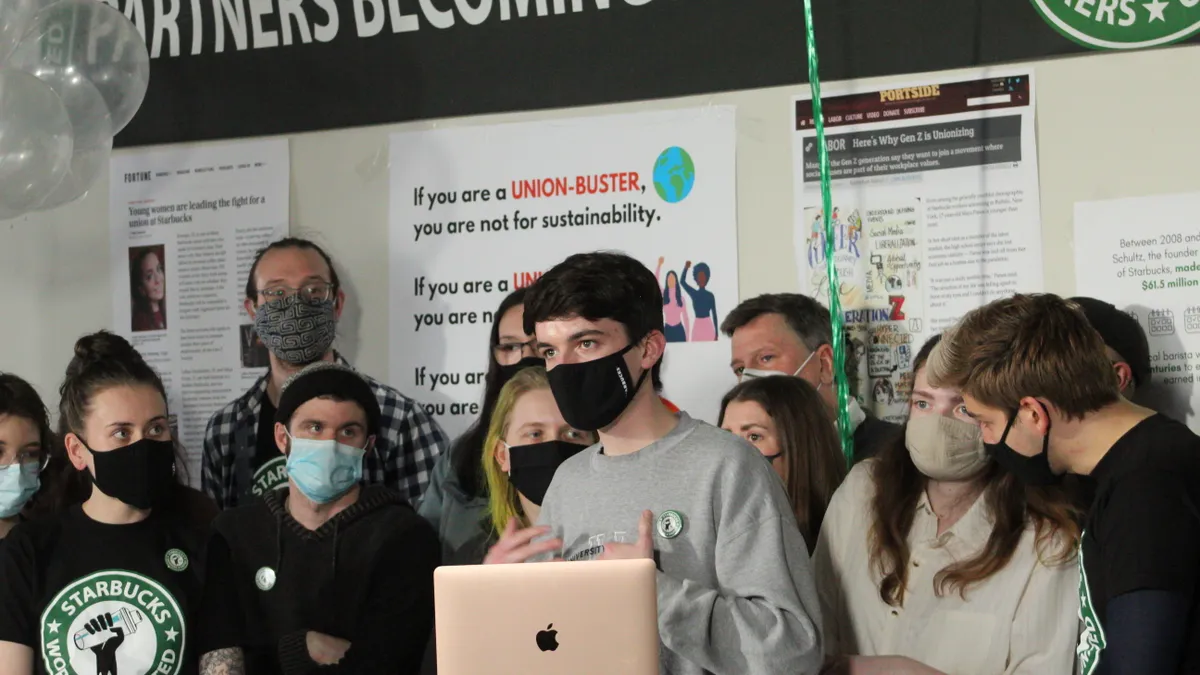

SBWU developed its proposals from the results of a bargaining survey carried out over the summer by its 60-person national bargaining committee. The committee works with regional committees, single-store bargaining committees, the union’s full-time staff and lawyers to ensure proposals are desired by workers across the board, SBWU national bargaining committee member Megan Brown said.

Starbucks, by contrast, has issued no public statements detailing bargaining goals with the union. A Starbucks representative declined to comment on what the company would want out of a contract.

Still, experts on contract negotiations say companies often seek especially wide latitude in management and personnel decisions.

“The most important thing from management's points of view is the management rights clause,” Gay Semel, a retired labor lawyer for the Communications Workers of America, said. “The only restrictions on their power is the union contract.”

Most contracts contain a section outlining the rights of management in discipline and termination procedures, and over workplace conditions generally. The stronger that section is, the more desirable the contract is from corporate’s perspective.

Sid Lewis, an employer-side labor lawyer and union consultant, agrees, noting expansive powers for employers make it possible for businesses to change operations more rapidly.

“[Management generally] wants a strong management rights clause. It wants to be able to transfer employees, hire and promote employees, you know, run its business as efficiently as possible without any red tape,” Lewis said.

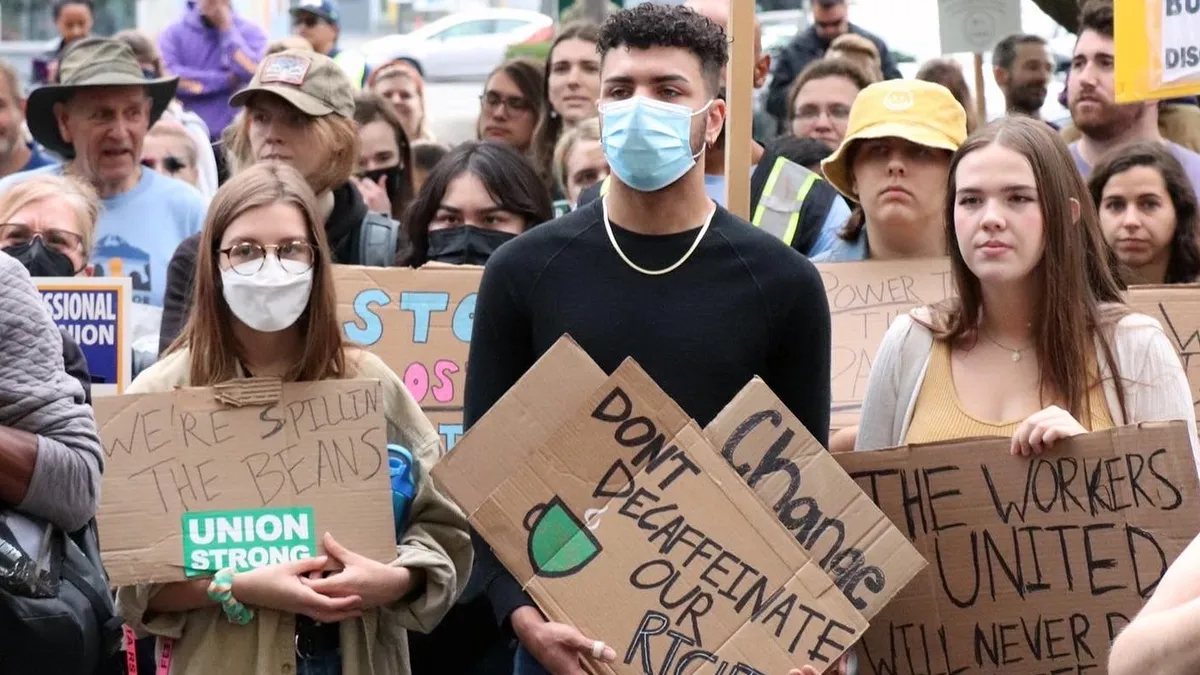

But much, or all, of SBWU’s proposals could be at odds with Starbucks’ contract goals. Organizers at stores in Washington, D.C., Buffalo, New York, Illinois and Massachusetts, as well as full-time staff of Workers United, told Restaurant Dive what they hoped to achieve in negotiations.

Above all, unionized workers want more power at their workplace

Unionized workers who spoke to Restaurant Dive want influence over their working conditions, from the company’s culture to its apron laundering policies.

Union organizer Aleah Bacetti said the most important proposal to her is the union’s nondiscrimination proposal, which bans discrimination based on a variety of factors, including race. The proposal also exempts workers from handling food that conflicts with their religious principles, as Muslim and Jewish workers are currently asked to handle pork products.

The program also expands Starbucks’ nondiscrimination trainings, which the company made a point of highlighting after a series of racist incidents in stores. Bacetti said training didn’t go far enough, and argues the union’s proposal, which requires managers to undergo inclusivity training at least once a year, could be important in stopping racial discrimination.

Bacetti, a Black woman, claims she was fired in part for her union organizing activities and in part for using the African American Vernacular English version of the n-word in conversation. In an email to Restaurant Dive, Starbucks said Bacetti was fired for violating “Starbucks’ Anti-Discrimination and Anti-Harassment Standards.”

“I was just speaking in AAVE. It wasn't even derogatory. It was a language that I can speak in because I'm Black,” Bacetti said. Bacetti and other Black workers at her store have faced racism from customers, including a White customer who, according to Bacetti, screamed the n-word at workers. Shift managers present did not ask the man to leave, Bacetti said, until he made a Black worker cry.

“The guy wasn't gonna get banned, because they didn't care. It wasn't at anyone else's expense, but the people of color,” Bacetti said.

Tae Cunningham and Sam Shields, Starbucks baristas and SBWU members, also discussed incidents in which customers made workers feel unsafe and in which management declined to kick customers out or to de-escalate situations.

Starbucks said it has a policy in place to deal with disruptive or unsafe customers, which entails the workers asking the person to stop behaving in an objectionable manner. The company said continued disruptive behavior can result in the customer being asked to leave, or in the company banning them from returning to its stores. The union has called on the company to allow employees to refuse service to customers who threaten workers.

Bacetti also claims shift managers mistreated and talked down to Black workers, and sometimes tried to withhold breaks, which they are legally entitled to, from Black workers rather than making adjustments to staffing. Starbucks said all reported violations of its anti-harassment and discrimination policies would be investigated fully. Bacetti said she did not file a report with the company because she feared retaliation from managers, who Bacetti said would know about a report.

“That's hard to do when your shift manager is a person you have a problem with because of racism,” Bacetti said. “They're gonna laugh in your face.”

The union is also calling for a “Just Cause” clause, which would give workers some protection against firings and implement a clearer process for discipline and written warnings.

“Starbucks has demonstrated they can fire partners for any reason, at any time,” said Julie Langevin, a Starbucks shift manager and member of the union’s national bargaining committee. “You could be doing nothing wrong and get fired or that you could make the smallest perceived infraction and be fired over that.”

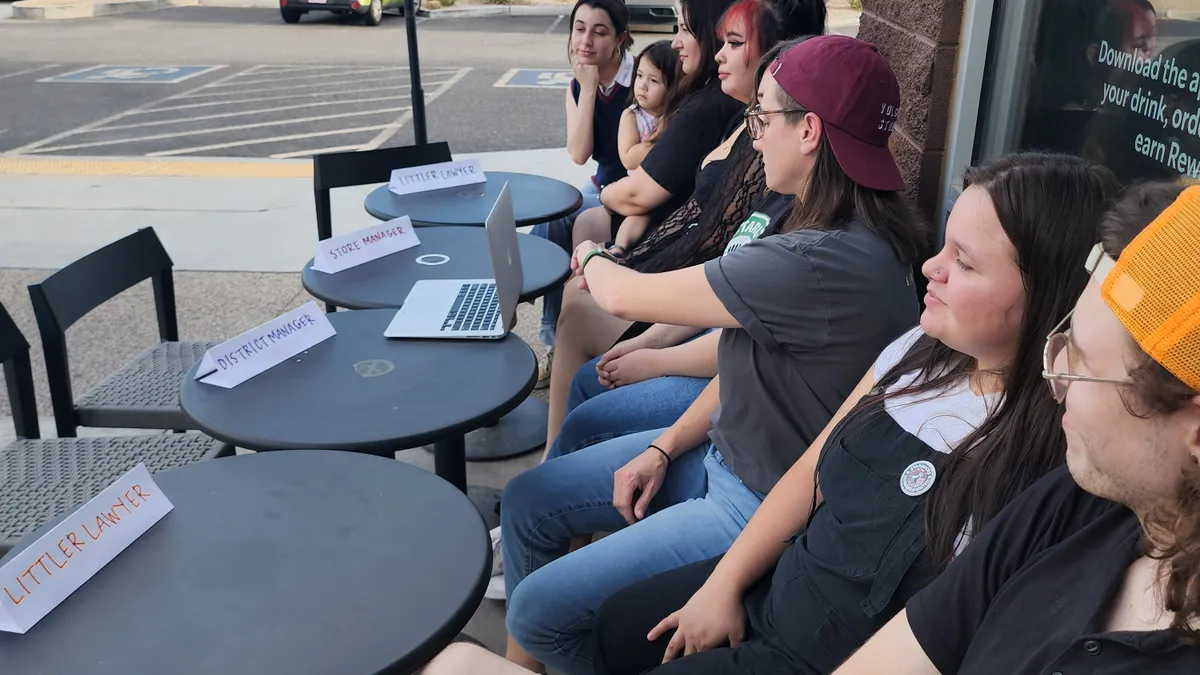

Another way SBWU wants to transform the company’s management is by building labor-management committees. This proposal would establish monthly meetings between store managers and union workers to discuss and resolve workplace issues, said Megan Brown, Starbucks barista and SBWU national bargaining committee member. The proposal is also the union’s counter to the sort of strong managerial rights clause that labor law experts expect Starbucks to seek in a contract. The labor-management committee would allow the union and the company to solve workplace issues before they become a problem, Brown said.

But one of the union’s most radical demands is also one of its oldest. The union’s fair election principles, a set of demands that would make it easier for workers to organize, first circulated in Aug. 2021, and were the first noneconomic proposal put forth by the union in this round of bargaining. This current iteration would also extend any contract or collective bargaining agreement from currently unionized stores to newly organized stores nearby. What these proposals amount to, for organizers, is a form of durable power.

“What we're really doing is creating a democracy in one of the richest corporations,” Kylah Clay, a barista and union leader in Boston, said. “This gives us a renewed sense of ownership of our workplace.”

Starbucks’ deep pockets may make bargaining harder

Starbucks Workers United members said the union has faced trouble organizing new stores after a number of union supporters lost their jobs. The union’s internal estimate, according to Buffalo-area barista Casey Moore, is that more than 120 union supporters have been fired or forced out of work.

Starbucks has maintained that all workers fired during the course of the campaign were terminated for violations of policy, but federal courts have begun to side with the union, ordering the reinstatement of a number of workers.

Starbucks has faced further NLRB scrutiny over benefits changes. Once a union is certified, management cannot change working conditions without bargaining, at least not legally, Semel said.

Earlier this year, Starbucks refused to extend new benefits to union workers, arguing it needed to bargain with the union over those changes. But Workers United waived its right to bargain on this issue in the hope that unionized employees could access the benefits. Starbucks has not bargained with SBWU, and has not awarded the new perks to unionized workers, either – frustrating SBWU and drawing criticism from the NLRB.

A regional NLRB office issued a complaint alleging Starbucks was withholding the benefits changes with the intention to dissuade employees from unionizing. The union said those benefits changes were inspired by demands articulated by its members. But even with NLRB as a watchdog, the SBWU is still very vulnerable to Starbucks’ power.

If SBWU reaches a contract with Starbucks, any such agreement would likely curtail the union’s freedom of action. The duration of the contract matters, Lewis said, as no-strike clauses — which are nearly universal in American union contracts — mean the employer has a period of labor peace for the duration of the agreement. Most contracts span three to five years, Lewis said, and many employers prefer the longer option, because it spaces out battles between management and labor and mitigates the possibility of a strike.

“[They] don't have to worry about any kind of strife other than the normal grievances, and maybe an arbitration [process for disputes] now and then,” Lewis said. “It’s peace for 5 years.”

Semel said smaller employers tend to be willing to settle for extended periods of labor peace, but larger companies with deep pockets, like Starbucks, may be less amenable.

To give one example, SPoT coffee, a Buffalo-based regional chain, saw workers move to unionize at several cafes in spring of 2019. Workers United won that election in August 2019 and agreed on a contract with SPoT by March 2020, according to Barista Magazine.

A larger company may never reach an agreement with a union, and may never offer a contract improving working conditions, though the NLRB sometimes regards that sort of bargaining as an unfair labor practice, Semel noted