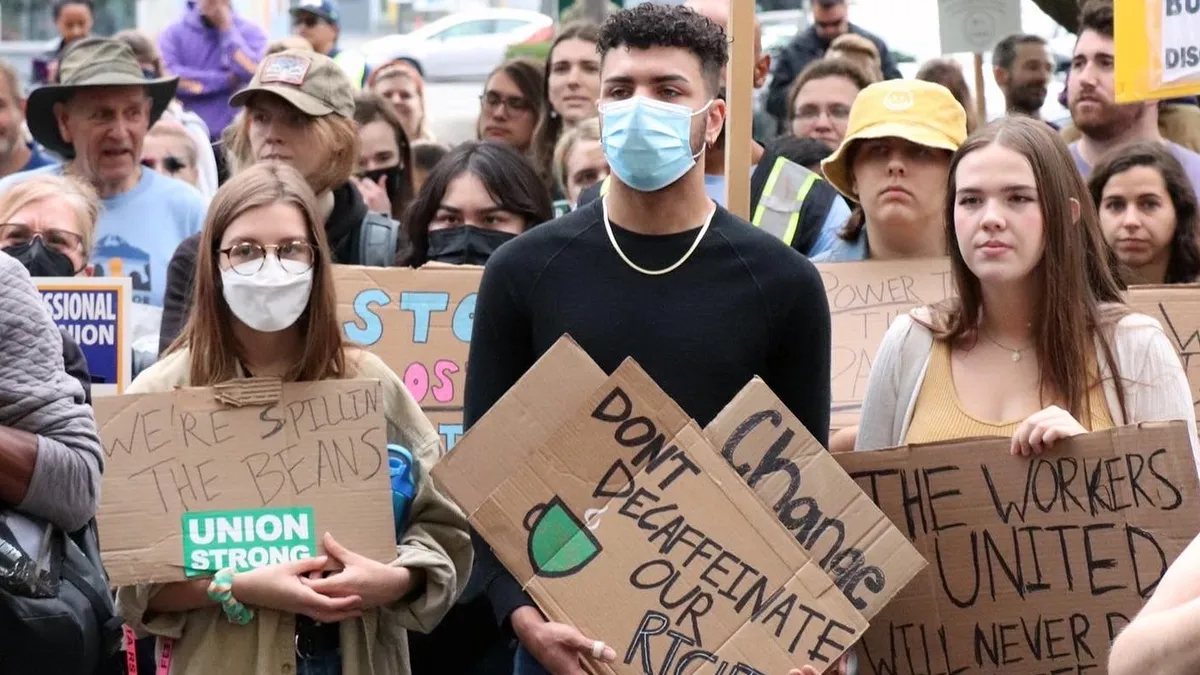

On Friday, the Starbucks union launched the longest national action of its campaign so far: 60 stores went on strike for three days, and 40 more staged walkouts for at least part of the weekend. This was Starbucks Workers United’s second major strike within a month, following Nov. 17’s one-day strike at about 110 stores.

On Dec. 14, the union announced a campaign to persuade customers not to buy gift cards this year. Unused gift cards and money loaded onto the Starbucks app boost the company’s profitability — funds accounted for $196 million in revenue for Starbucks in the last year, according to Starbucks’ 10-K.

The combination of a targeted product boycott and multi-day strikes at stores across the country constitutes a strategic escalation by the union to push Starbucks toward the bargaining table, workers and labor experts say.

“We’re doubling down on fighting back,” Elizabeth Duran, a pro-union barista at Starbucks’ Seattle Reserve Roastery, said. “[It’s] the next step in escalation from our strike we did in November… the idea is that [Starbucks is] just going to keep using the same tactics against us. So we’re going to keep escalating until they start taking it seriously and they come to the bargaining table.”

Less than 1% of company-owned stores went on strike for all three days, but the goal of the walkouts isn’t necessarily to hurt Starbucks financially, labor experts say.

“There’s more than one purpose here. Clearly, the strikes are intended to highlight and bring attention to Starbucks’ unlawful anti-union campaign,” said John Logan, chair of the labor and employment studies department at San Francisco State University’s Lam Family College of Business.

Another motive, according to Nelson Lichtenstein, the director of the University of California, Santa Barbara’s Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy, is to keep workers engaged in the campaign and get them used to taking collective action without risking a potentially catastrophic open-ended strike.

“We’re going to keep escalating until they start taking it seriously and they come to the bargaining table.”

Elizabeth Duran

Pro-union barista, Starbucks

“[Limited strikes] tells the management that this is a committed group of workers. And a limited duration strike builds solidarity and elan and good feeling among the workers,” Lichtenstein said.

That good feeling, Logan said, may help SBWU maintain shop floor strength and dynamism despite high turnover and challenges with corporate. The union has accused Starbucks of engaging in unfair labor practices, including retaliatory firings, targeted closures, deliberate understaffing and offering workers benefits to dissuade them from organizing. Starbucks denies employing those tactics.

The strikes, and accompanying messaging, are a test of SBWU’s ability to influence consumer behavior and damage Starbucks’ brand, which Licthenstein said was a key element of Starbucks’ power.

“A brand is a way of creating monopoly,” Lichtenstein said. Consumer identification with the Starbucks brand depends on the company’s adherence to perceived values, Lichtenstein said, and produces an affinity that goes beyond the material qualities of specific products.

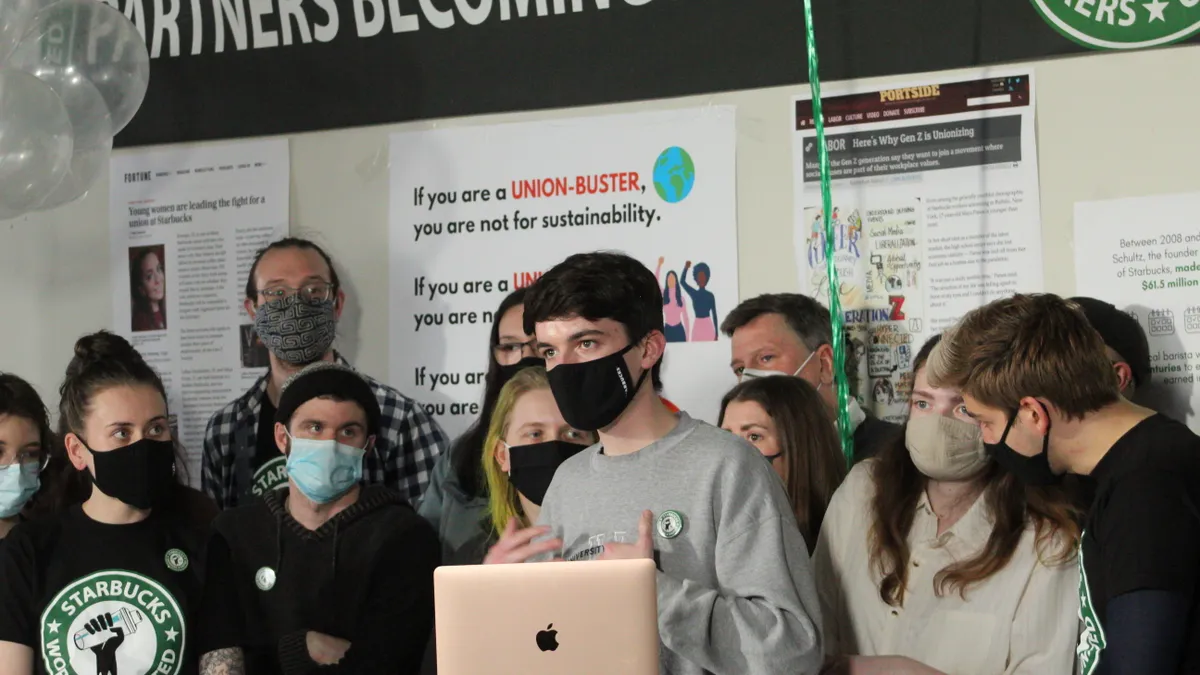

Starbucks’ attempt to foster a progressive, inclusive brand extends even to the language the company employs to dissuade workers from unionizing, Lichtenstein said. One.Starbucks.com, the website the company has built to counteract the union’s online presence, emphasizes the idea that workers currently can communicate directly with management, and argues that collective bargaining disrupts a direct relationship between employees and management.

Damaging the brand, through corporate campaigning, limited strikes and a constant trickle of media coverage regarding alleged unfair labor practices, could give SBWU leverage over the company despite the union’s small scale compared to Starbucks’ nationwide footprint.

Both Logan and Lichtenstein mentioned the United Farm Workers’ effort to organize several consumer boycotts of table grapes between 1965 and 2000 as an example of a campaign that generated lasting changes in consumer behavior.

“If you ate grapes,” Lichtenstein said. “You were against the farmworkers.”

Lichtenstein said Workers United may pursue a similar strategy around Starbucks gift cards, seeking to turn them into a culturally distasteful product.

A protracted campaign or boycott, Logan said, could be successful if SBWU manages to enlist the participation of the institutional labor movement. At rallies around the country on Dec. 9, members of other unions spoke in support of Starbucks Workers United and urged consumers not to buy gift cards. Liz Shuler, president of the AFL-CIO, the country’s largest labor federation, spoke in favor of SBWU’s campaign at a rally in Arlington, Virginia. She also decried the company’s alleged anti-union practices.

“A brand is a way of creating monopoly.”

Nelson Lichtenstein

Director, University of California, Santa Barbara’s Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy

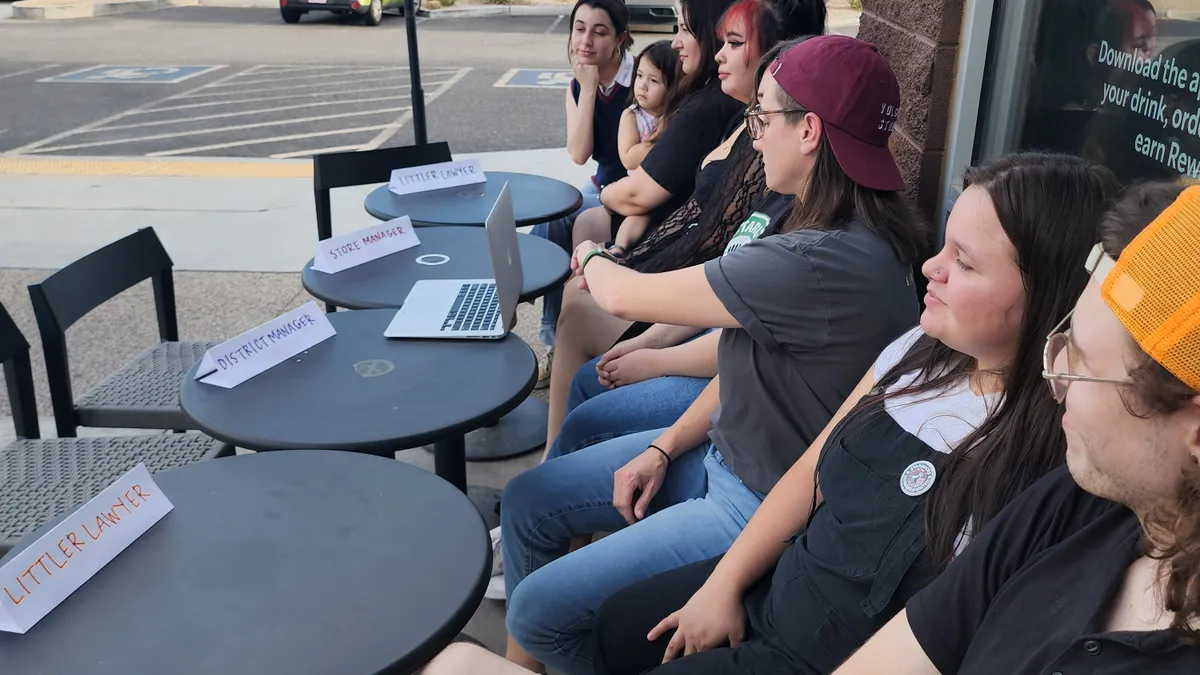

Starbucks Workers United has accused Starbucks’ of retaliatory store closures, firings, and of failing to bargain in good faith, among other actions. Andrew Trull, a Starbucks spokesman, said Starbucks has closed 38 company-owned stores in the U.S. since July 2022. Only 10 of those stores, Trull said, had union representation, and they were closed over reported safety concerns, including theft, drug use and vandalism.

Less than 3% of company-owned U.S. Starbucks stores are unionized, but 26% of stores closed due to safety concerns this year were unionized. Trull declined to speculate as to the cause of this disparity. To Starbucks Workers United members, it’s a sign of retaliation.

Starbucks, according to Trull, applies the same safety standards to union and non-union stores when determining which units to close. But union members allege the latest closure of the Broadway and Denny Starbucks in Seattle was retaliation for the union’s strikes on Nov. 17.

“After we struck over 100 stores for Red Cup Rebellion, Starbucks doubled down on their union busting by closing the Broadway and Denny store in Seattle,” said Casey Moore, a barista and SBWU member who works on the campaign’s communications