David Nayfeld didn't want to risk reopening Che Fico, the independent Italian restaurant he co-owns in San Francisco, for most of the pandemic. Labor was hard to come by, and there was no guarantee new COVID-19 variants or restrictions wouldn't gut the business.

Before the coronavirus crisis, Nayfeld's operation employed about 100 workers. When it finally reopened fully in late October, that number was closer to 60. Nayfeld was unable to bring staffing up to previous levels because it takes a long time to find workers who fit the restaurant's culture and have the soft skills needed for their jobs.

Then from December to January, a quarter of his workers contracted the virus.

"The worst thing possible has happened," Nayfeld said.

New variants stalled the recovery

For many restaurateurs, labor and sales recovery stalled out in the second half of 2021, according to Hudson Riehle, senior vice president of the National Restaurant Association's research and knowledge group.

"When you look at restaurant industry sales growth in the second half of 2021, that sales level basically remained essentially flat from July on," Riehle said. "The same is also true for restaurant industry employment."

The delta and omicron variants have dealt the restaurant industry a serious blow. The surge in coronavirus cases in late December drove down sales by more than half at nearly 60% of 1,200 restaurants surveyed by the Independent Restaurant Coalition. OpenTable data also shows a gradual fall in on-premise dining traffic in December compared to the same period two years ago.

Labor in the foodservice space has similarly dragged. About 650,000 fewer workers are currently employed in foodservice than in January 2020, and the sector has seen only gradual increases in employment since July 2021, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Meanwhile, the NRA expects consumers' disposable income, adjusted for inflation, to shrink in 2022 in the absence of further stimulus from the federal government. This decline in spending power would lead consumers to be choosier, even though diners still want to go to restaurants, Riehle said. Flat sales and flat demand, he indicated, could mean flat employment.

Elise Gould, a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute, expects the headwinds caused by the omicron variant to be less persistent than what followed the delta variant, as case loads may fall faster, and omicron is likely milder than delta. Despite increased turnover, Gould noted, hiring has also kept pace with separations.

"We've seen record high numbers of quits in the last couple of months," Gould said. "And yet, hires are keeping up."

The number of workers employed in foodservice increased by about 40,000 between November and December, according to BLS data. Gould said the impact of the omicron variant on jobs would not be fully clear until BLS data for January comes out next month.

"We're gonna see [declining to flat jobs growth] in January, and maybe even February, because of omicron. But I hope that we will get on the other side of that and continue to see job growth over the months following," Gould said.

2022 is likely to see a gradual increase in the number of workers employed in foodservice, driven by recovering sales and improved offerings from restaurant employers, said Ted Lynch, managing director for restaurant banking at Bank of America.

"There'll be a gradual pickup, the bodies will come back online, [labor] expenses will come back up on a per person, hourly basis," Lynch said. "But hopefully there'll be a natural process where things get smoothed out."

Nayfeld is less optimistic. Independent restaurants, especially those that did not receive Restaurant Revitalization Fund grants, have faced mounting supply costs and rising rent — pushing many to take on large amounts of debt just to stay open. The uncertainty of the labor market will hurt independents more than major brands, Nayfeld said.

"We are dealing also with a historically challenging labor force," Nayfeld said. "People are worried about our industry. People genuinely think to themselves, 'Should I go back to work at a restaurant? What if that restaurant has to lay me off again?'"

Benefits, wages and safety are key to retaining workers. But many operators are struggling.

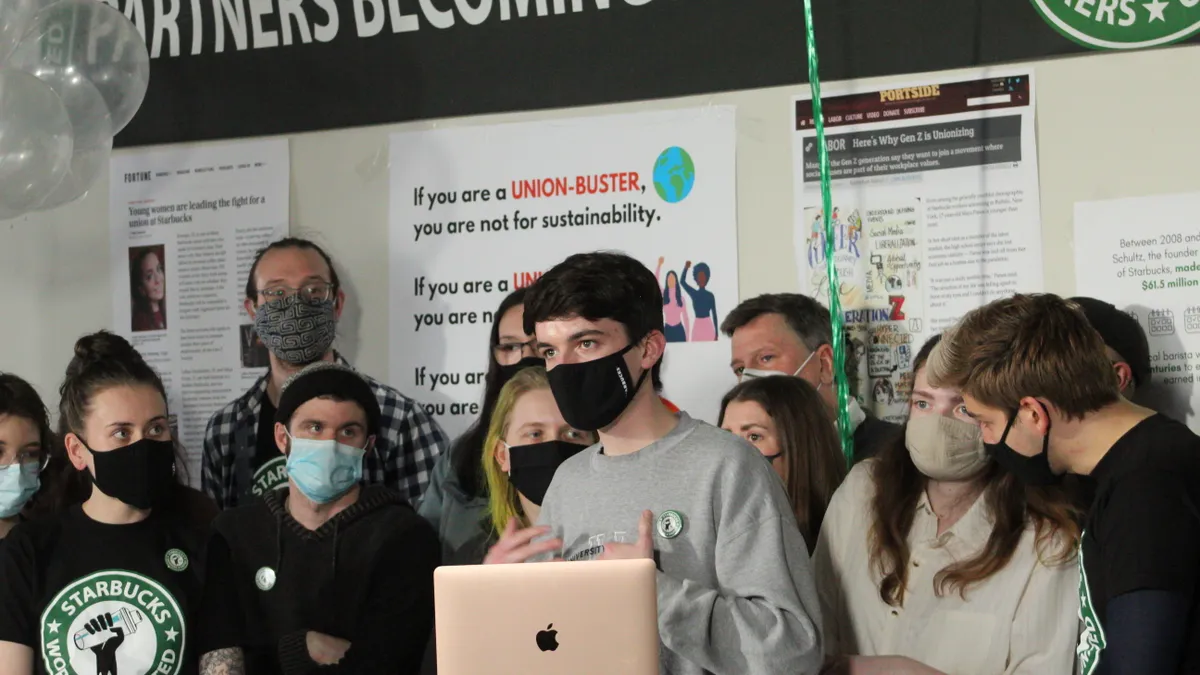

High turnover, a relatively low unemployment rate and the reluctance of workers to enter the restaurant industry has put upward pressure on wages, with many restaurants turning to wage hikes or new benefits to attract and retain talent. Chili's parent company, Brinker International, is boosting hourly pay to $18 an hour including tips by 2023, and is focusing on filling managerial roles with internal candidates. Starbucks has accelerated ongoing wage increases, and other major chains have rolled out signing bonuses and new benefits.

A combination of increased compensation and better benefits could attract more hourly workers, but that's a tall order for many independent operators. And many workers are looking for employers who offer something beyond higher pay, according to Lynch.

The companies that are succeeding in attracting new workers, Lynch said, are those trying to create a fun work environment and build a shared company culture alongside opportunities for professional growth.

Sekou Siby, president and CEO of Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, a nonprofit focused on organizing restaurant workers, agrees that wage gains alone haven't been sufficient to draw workers in.

"Workers are not benefiting from the wage increase because prices are actually going up," Siby said. "It is driving the workers out of the restaurant industry."

Siby said restaurants are competing with other employers for low-wage workers, including Amazon, which offers $15 an hour. The risks of contracting COVID-19 has also made some employees wary of returning to work in restaurants at the prevailing wage, Siby said.

"Businesses are not thinking, restaurants especially are not thinking, of increasing wages based on the amount of risk," Siby said.

"Workers are not benefiting from the wage increase because prices are actually going up. It is driving the workers out of the restaurant industry."

Sekou Siby

President and CEO, Restaurant Opportunities Centers United

Nayfeld argued that without a refill of the RRF — which closed to applications in May — it will be difficult for independent restaurants to prioritize worker safety and do right by employees if businesses shut down due to COVID-19 case surges.

"Sometimes things are bigger than the business," Nayfeld said. "People's safety is bigger than the business. But that's … why we need the federal government to step up and do their part to allow us to continue making good choices."

Employers who respond to the shortage by asking more of their workers may risk driving people out of the industry, Gould said.

"If they're … making people come to work when they [are] positive [for] COVID-19 or [have] COVID-19 symptoms because they're concerned about not having enough workers, then maybe they should be doing other things to attract and retain workers," Gould said. "Maybe they can attract other workers to fill those slots, and pay more and provide better working conditions and paid sick days."

Companies that have historically managed to keep turnover low have performed the best during the pandemic, Lynch said. Nayfeld said his restaurant has managed to retain some of its workers largely thanks to goodwill he accrued by offering paid sick leave, covering the cost of health insurance for laid off workers and paying for his employees’ COVID-19 testing. Research from One Fair Wage indicates that paid sick leave, better health insurance and other benefits could keep workers from leaving the foodservice industry.

A shift toward off-premise dining and labor-saving technology could improve labor productivity or reduce staffing needs, Lynch said. The cost savings that come with these pivots have allowed the industry as a whole to remain profitable.

"Everybody was forced to make themselves more profitable," Lynch said. "It'll be baby steps to get back to where we were, in terms of real full employment."