Across the country, more than just coffee is percolating at independent cafes. Workers at dozens of cafes in cities from Seattle to Boston have teamed with at least four major unions, giving organized labor a foothold beyond Starbucks Workers United’s highly visible — and groundbreaking — union success.

While still small, unions in the coffee sector may be poised to transform working conditions and operations in many markets. This gradual rise in unionization is being driven both by general restaurant working conditions and issues that are specific to the cafe sector.

While some sub-industries — hotel kitchens, institutional foodservice, airport and stadium foodservice, and casino dining services — have higher union densities, traditional restaurants are effectively a non-union industry. Before Starbucks Workers United, the closest thing chain QSRs had to a national union was a five-store Burgerville bargaining unit. Only 1.4% of workers in the foodservice industry are union members, among the lowest of any job sector, down from mid-century highs of about 25%, a decline driven by general declines in unionization, the growth of franchised restaurants and QSRs, and several disastrous strikes in the 1980s.

So why are cafes becoming a key labor battleground?

Coffee regulars can become union supporters

Coffee shops can be an ideal incubator for labor organizing because these businesses typically have low wages and poor benefits, said Todd Vachon, assistant professor of Labor Studies and Employment Relations at Rutgers. Such factors, combined with unpredictable scheduling and strong social bonds between employees, can prime cafe workforces for union acceptance.

“Young people often go to work where their friends also work. There is that kind of built-in social connectivity,” Vachon said. “These workers are younger and more educated, and probably have college debt, and it's a recipe for this sort of [union] activity.”

Strong relationships with local customers give employees at neighborhood businesses an advantage over those at national brands, because they can turn to their regulars for support, said Dorothy Sue Cobble, an historian of the labor movement in the service industry.

“The customers were really important allies in organizing,” Cobble said. “One of the real [organizing] advantages that one could have in working at smaller cafes, is that you had a lot of control over your customer interactions. And you had customers that you knew, for a long, long time, and you developed these bonds.”

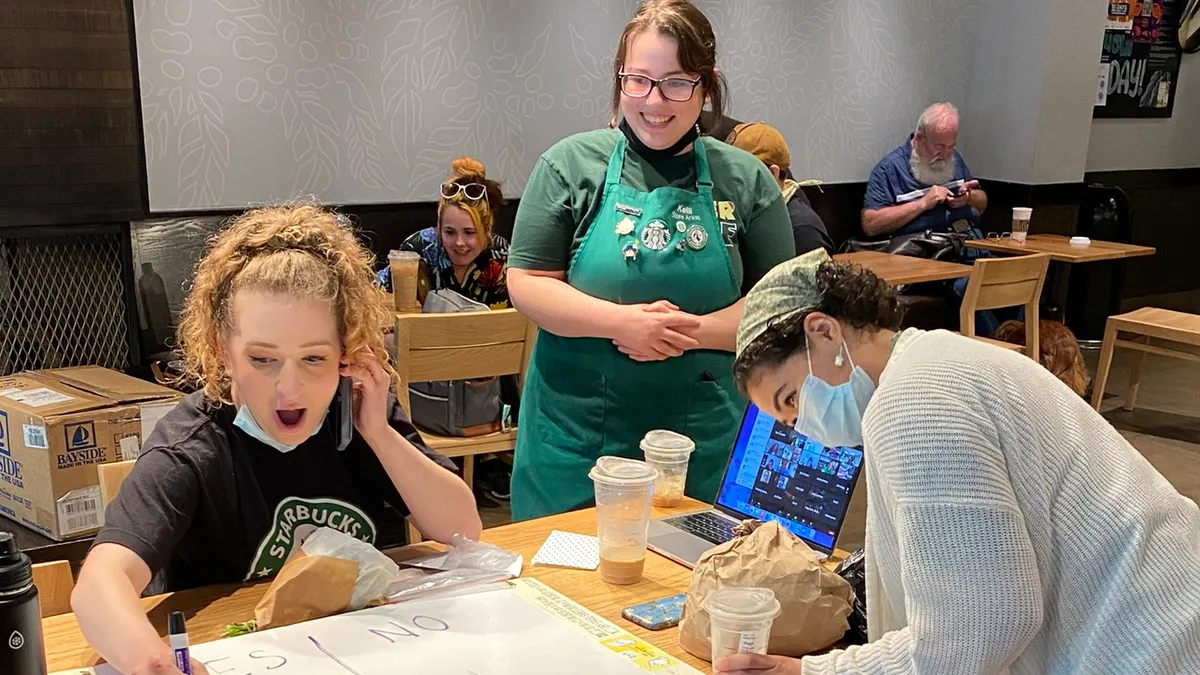

Given that coffee is a habitual purchase, support from regular customers may be more easy to find in cafes, where workers may have long-standing, deep connections to their customers. Eoin Jaquith, a barista at 1369 Coffeehouse in Inman Square in Somerville, Massachusetts, said organizing has changed the way customers see workers at 1369.

“I ended up talking to a lot of our customers about what was going on. A lot of them are grad students who recently went through union drive at MIT,” Jaquith said. “It put into perspective that this is a larger fight than one industry for a lot of us.”

Larger restaurants and full-service restaurants, Vachon said, tend to have stark divides between the back-of-house and front-of-house staff that can prevent solidarity between workers in a restaurant. That’s generally not the case with cafes — a difference that can foster stronger bonds among organizers.

“The workers in the kitchen are often immigrants, people of color or people that are not native English speakers, and the front-of-the-house [workers] are more traditionally, white or European origin,” Vachon said. “Cafes definitely have a little bit less of a distinction. Everybody's doing essentially the same work.”

Why now?

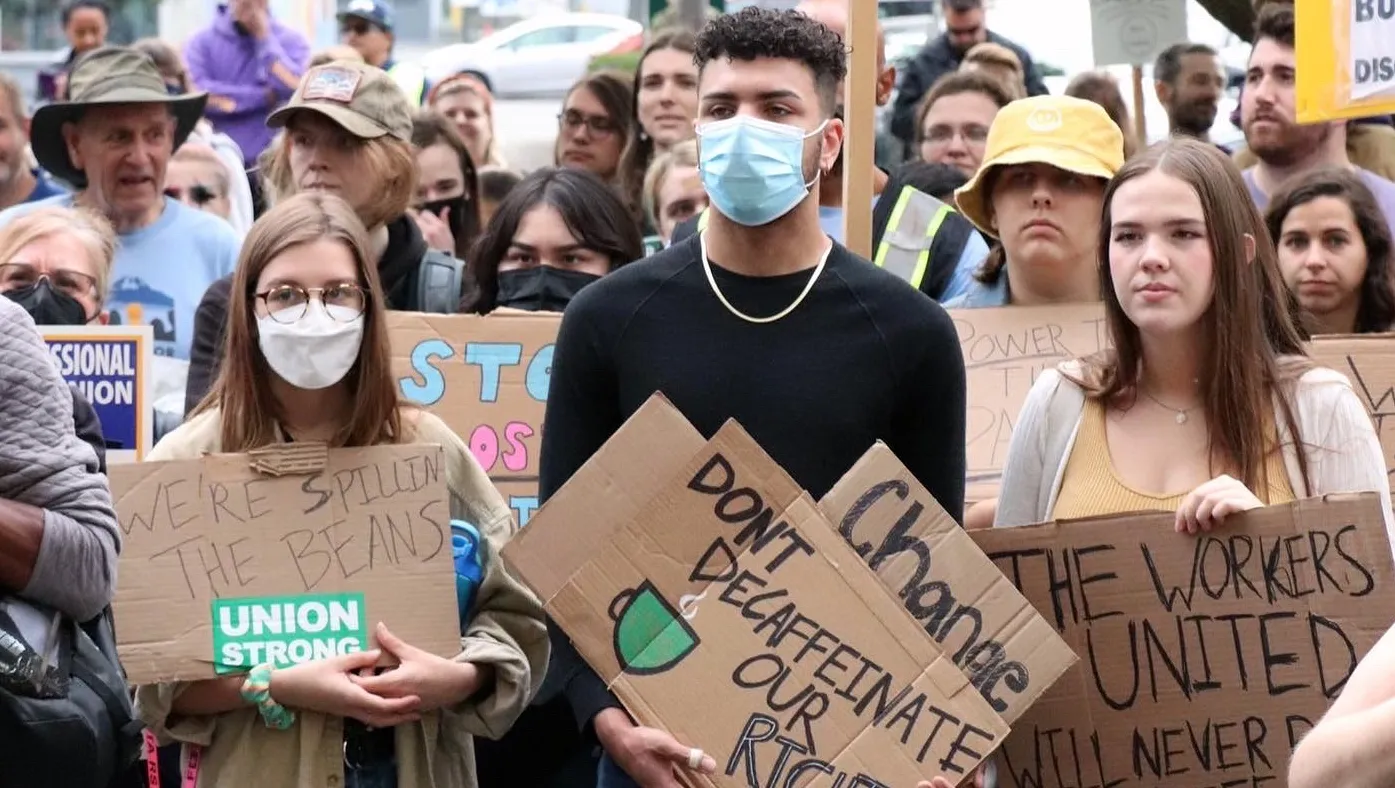

The subjective factor that could explain the rash of recent organizing, Vachon said, is that workers are seeing other employees in the same industry organize and sometimes win, including baristas at Starbucks. Workers at smaller cafe chains like Gimme Coffee in Ithaca, New York, are also notching wins.

Will Westlake was a member of the organizing committee at Gimme Coffee and later salted — meaning he took a job at a non-union workplace with the intention of organizing — a Buffalo-area Starbucks for Workers United. Westlake said the Gimme Coffee union faced a decertification campaign after the company laid off most of the union workers due to COVID-19. But before the pandemic, Westlake said, workers won some considerable demands, which helped spur organizing at other cafes in western New York, including Starbucks.

“We organized and we got a contract. And it only took about six months, and all of a sudden, all of my co-workers were making $5,000 more a year or $6,000 more a year, purely because they were able to get together and organize,” Westlake said.

Such victories could push workers at other stores to organize. At Jaquith’s workplace, organizing at other cafes helped spur employees to unionize.

“We were looking around at other shops around us who had gotten raises through the union, who had gotten better health insurance or health insurance [for the first time], through the union,” Jaquith said.

What’s in it for the workers?

The timing and conditions that led cafes to start unionizing are clear, but the personal motivations and identities that help create coherence among workers are complex. A lack of hard data on workforce demographics across cafes makes it difficult to say which groups of workers are organizing and for what reasons.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data for the cafe sector provide a relatively incomplete picture of cafe workers, with such workers largely counted under the broader Food and Beverage serving and Related Workers classification.

Starbucks, the largest employer of baristas in the United States, conducts a yearly analysis of some demographic information, which is a limited, if useful, proxy for industrial demographics as a whole. According to Starbucks’ numbers, 82% of its retail-level employees are below the age of 30, 73% of its retail workers are female and 53% are people of color. According to one survey, more than one-third of the chain’s retail employees identify as LGBTQ.

John Logan, chair of the labor and employment studies department at San Francisco State University’s Lam Family College of Business, said these demographics – young, often college-educated, often LGBTQ workers – have been more likely to unionize than other demographics in recent years. Part of this may be the cohesion created by workers wanting to work alongside friends or in places they feel safe, Logan said.

Each union drive results in more workers with experience organizing. This may make workers more likely to organize other workplaces, even when initial efforts fail. Jaquith was part of a failed organizing drive in Rhode Island, but remained open to unionizing at 1369 out of a commitment to his co-workers.

“I don't think I would have done it for me alone,” Jaquith said. “But I’d absolutely do it for my coworkers.”

What are the ripple effects?

All these factors may lead to further organizing in the cafe space, especially as unions build strength in specific cities and win contracts in some workplaces, though Logan noted that the growth of foodservice unions is likely to be slow.

“For certain kinds of unions that understand the workers, that understand the industries, and are capable of running campaigns based on worker self organizing, this is a really big opportunity,” Logan said. “It's going to take dozens, if not hundreds of campaigns, like Starbucks Workers United.”

For workers like Westlake, that transformation of the industry, regardless of its duration, is the point of industrial action.

“I grew up in the service industry. My mom was a restaurant manager for 20 years,” Westlake said. “She didn't have health care. She was diagnosed with stage two cancer. She spent most of her savings trying to fight it, and died having no money.”

“There is an obligation to take care of people, especially when they dedicate their lives to a business. And there's millions of service workers in this country that are doing exactly that, [while] living paycheck to paycheck,” Westlake said. “The solution is going to be organizing.”