When the leaves have turned and the highs have slipped from the summer’s hellish heights down to more reasonable temperatures, people can go into a coffee shop and buy a drink that evokes key signifiers of the holiday season: family, the comforts of home, the chill of autumn.

At Peet’s Coffee, customers can find caffeinated mocktails designed with winter flavors. The brand’s winter lineup for 2024 boasts the Derby, a mock-Irish coffee; the Bestie, which contains orange bitters, blood orange puree and chai-spiced tea; and the Tiger’s Eye, which mixes blood orange puree, cold brew, orange bitters and club soda.

Dutch Bros, meanwhile, includes a host of time-limited drinks. The 950-store coffee chain has embellished its menu with Candy Cane and Hazelnut Truffle Mochas, and a blue raspberry sweet cream version of its Rebel energy drink. It’s enough to give Scrooge visions of winters yet-to-come, complete with a caffeinated Tiny Tim buzzing beside a suitably modern pellet stove.

The evocative power of seasonal coffee drinks depends on a careful process of development, refinement and analysis. Before the first consumers taste orange puree or peppermint syrup, these ingredients have to be designed, tested, produced and distributed. Workers must be trained, marketing campaigns prepared and consumers primed before the first cup passes through the drive-thru window.

Companies like Dutch Bros, Peet’s and Westrock Coffee, which supplies many QSR and C-stores with coffee products, begin planning and testing their seasonal drinks far in advance.

Restaurant Dive spoke to these companies about the long process of planning, designing, testing and producing their seasonal coffees.

Planning and devising the flavors

Mike Mastio, Westrock’s senior vice president of technical services and research and development, said coffee companies are already looking towards flavors for 2026 and 2027. That’s because designing complex flavors is an arduous process that requires carefully balancing chemistry, nutrition, sensory elements, shelf-stability and ingredients.

But success in a lab doesn’t necessarily translate to success in production.

“It’s longer than you might think,” Mastio said of the development process for coffee LTOs. “A lot of the work is not presented at the time and you might not even have a business case for it. There may be 100 different flavors.”

For Kyle Newkirk, Westrock Coffee’s executive vice president of global sales and innovation, the design of a coffee LTO can begin as far as two years in advance. It starts with conversations about flavor priorities, LTO cadences and approaches to menu innovation with Westrock’s customers.

“You tend to have to have the final product of flavors and drink builds locked in as much as a year in advance of when they're actually going to launch,” Newkirk said, which leaves brands time to test and market their drinks.

Dutch Bros tries to keep its eye on trends in flavors, said Tana Davila, the brand’s chief marketing officer. The company tries to identify when flavors have reached a favorable point of adoption and uses a variety of tools to keep track of emerging ones. From conceiving of an LTO drink to deploying it typically takes around six months for Dutch Bros.

Peet’s does something similar, said Filipa Aguiar Loureiro, head of retail product marketing for the coffee company. The brand monitors flavor trends and then tries to capitalize on them with its seasonal LTOs. Peet’s marketing teams try to give its product teams about an eight-month lead time to develop drinks. This year, that meant making Mocktails.

“We see sobriety as being a big movement with younger audiences, and that's really who we're trying to connect [with] at the coffee bar,” Aguiar Loureiro said.

Part of Peet’s intent with its unconventional holiday coffee LTOs was to expand the range of dayparts and occasions for its drinks, Aguiar Loureiro said. Sweet, hot beverages like peppermint mochas, for example, make compelling breakfast drinks, but fruity, coffee-forward drinks, including cold drinks, tap into growing consumer appetites for caffeinated drinks throughout the day.

“We wanted to bring a bit more of a different time of the day, more of an afternoon thought, a different occasion, a bit more of a sophisticated flavor,” Aguiar Loureiro said. “It's really branching out to more territories and more moments of need.”

Orange bitters and blood orange puree are the centerpieces of two of Peet’s holiday drinks, taking advantage of citrus’ associations with the holiday season. The Tiger’s Eye, a sparkling drink, is designed to capture consumer demand for refreshers, while the Bestie supplements fruit flavors with chai, a blend of warm, aromatic spices.

“It's reminiscent of a mulled wine, or Gluehwein, a German drink. It’s very festive, like a mulled cider,” said Patrick Main, a senior manager of research and development at Peet’s.

Testing, production and training

But identifying trends and dayparts is only one part of the battle. The flavors in complex beverages, like Peet’s layered LTOs, have to work well together, a process which depends on the density of ingredients, Main said

“We have to think a lot about the specific gravity of different ingredients. How are those going to react with each other? Where are they going to sit in the cup? How easy is it for the consumer who wants to incorporate everything into one thing? How easy is it for the customer who wants to experience different layers,” Main said.

Most beverages are subject to complex chemical processes that impact flavor. Coffee, syrups, milks and fruit purees are all somewhat unstable, and even tap water’s chemical attributes vary by location. This, in turn, requires different formulae: packaged goods need to be shelf-stable for a period, while drinks prepared on-site need to maintain a consistently appealing texture and flavor for consumers.

Once Westrock has locked-in the basics of a flavor, or a set of flavors, Mastio said, the company enlists panels of supertasters who specialize in analyzing caffeinated drinks and can detect everything from over-roasted coffee to unpleasant, lagging creaminess. Further refinement follows before blind taste tests with general consumers.

Once the company has settled on a flavor combination, it has to make sure the recipe can be produced at scale, Mastio said. That process requires understanding how liquids behave as they move through the production process, given the scale of some factories.

“From the time I take it out of the heat exchanger to the time I put it in a tank, it is still doing something,” Mastio said. “And when you have hundreds of yards of pipes around there that all have various temperatures, you can see that there's effects.”

Designing modular drinks is a little easier. Davila said that at Dutch Bros, flavors that work in one part of a menu category tend to work across several drinks. Syrups or additives that go with one coffee-based drink generally go well with others, while flavors from energy drinks and refreshers tend to be interchangeable across those platforms.

Dutch Bros often tests its new drinks in shops to ensure consumers like the beverages and that the production process fits in with the existing workflows in a cafe.

Operations are a key consideration at this stage for Peet’s, too, and the brand tries to strike a balance between flavor innovation and simplicity and familiarity for its workers, Aguiar Loureiro said. For simple changes, like moving from Pumpkin Spice to Holiday Lattes, those changes are minimal, since both drinks use a standard latte build and flavored syrups. To support training, the brand distributes recipe cards to stores and provides training videos for more complicated new drinks, Aguiar Loureiro said.

Main, who started with Peet’s as a barista, said the brand’s innovation team includes many ex-hourly workers who are familiar with the layout and operations of a store, which makes it easier for the company to design new drinks and then integrate them with store operations.

“I don't have to imagine what it is to re-create a recipe in the moment in a busy coffee bar, I've done it,” Main said. “It's very direct for me.”

But integrating recipes with store operations requires Peet’s to get drinks to its store in advance of the launch date, with enough time to train baristas.

Marketing and preparing for launch

An LTO like Peet’s fruity coffee mocktails require more marketing muscle to alert consumers than other time-limited drinks.

The brand works through multiple channels, including PR and earned media, but with a special focus on consumer engagement and through its app. These efforts include teasing the drinks, elaborating on flavor combinations and builds, and efforts to promote trial.

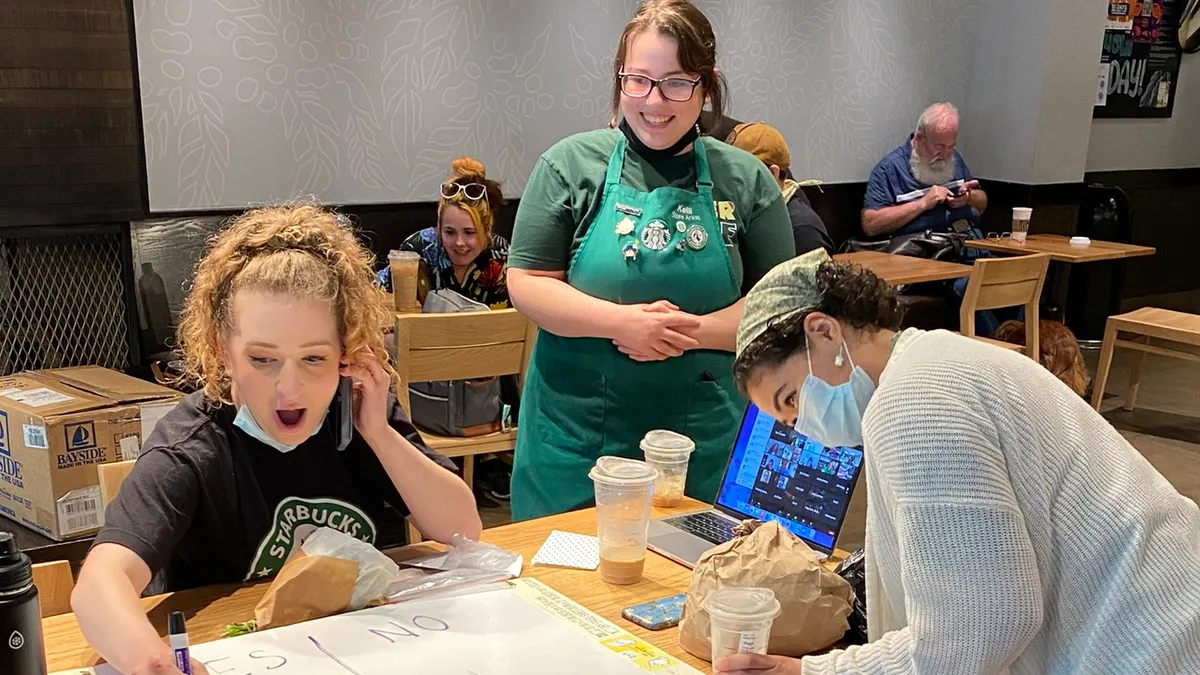

But Peet’s most important marketing channel for new beverages might be its frontline workers, Aguiar Loureiro said.

“There's no bigger ambassador than a happy barista,” Aguiar Loureiro said. “We also do some active sampling within the store as the season launches to spread some awareness and get those new flavors going.”

Westrock tries to finalize its drinks as much as a year in advance to give clients the time to “do all the photo shoots and the marketing and the consumer testing that they need to do,” Newkirk said. Actual production begins about three months before product launch, Newkirk said.

Dutch Bros has a strong presence on social media, Davila said, which makes it easy for the brand to roll out new menu items and LTOs.

“Our guests are waiting for new stuff from us,” Davila said. “People are even sometimes looking for little hints of what's coming, and often sending in lots of thoughts and suggestions on other things they would like to see from a product standpoint.”

Measuring the success of LTOs

After all those months of design, testing and refinement, Peet’s announced its holiday mocktail drinks in October and launched them in early November, while Dutch Bros also debuted its holiday menu at around the same time.

How do they know if the drinks were well-received?

Simple metrics provide robust answers, Davila said.

“I definitely look at absolute velocity, units per shop, per week or per day,” Davila said. “We have a very large and robust loyalty program. So I do look at the percent of loyalty guests that try an LTO. I think that's actually a good indicator of appeal.”

Davila said Dutch’s protein coffee, which launched last January, was a good example of a breakthrough item. Those beverages, which have about 20 grams of protein, create something of a new menu category for the company because of its nutritional profile. The protein-heavy drinks were so successful Dutch Bros brought them onto the main menu.

At Westrock, success is likewise easy to determine. If customers want more, or if Westrock needs to expand production, the company knows it has a good drink on its hands, Mastio said.

“The biggest indicator is if they keep ordering,” Mastio said.

Once Westrock knows it has a hit, Newkirk said, it’s often easy to plan for the future.

“We will just plan at that point to reschedule it for the same planning window for the following year,” Newkirk said. “Or if it didn't hit sales volume needs we'll either make tweaks to the formula or come back with another flavor.”

While Peet’s analyzes raw sales, according to an email statement sent to Restaurant Dive, the brand also looks at qualitative feedback and brand buzz, since total sales may be an imperfect measure of a drink’s deeper connection with specific consumers.

“Even if an LTO doesn’t achieve the highest sales, we consider it a success if it leaves a lasting impression and connects with our target audience as intended,” a Peet’s spokesperson wrote.